Points of View

Proposals for classroom projects

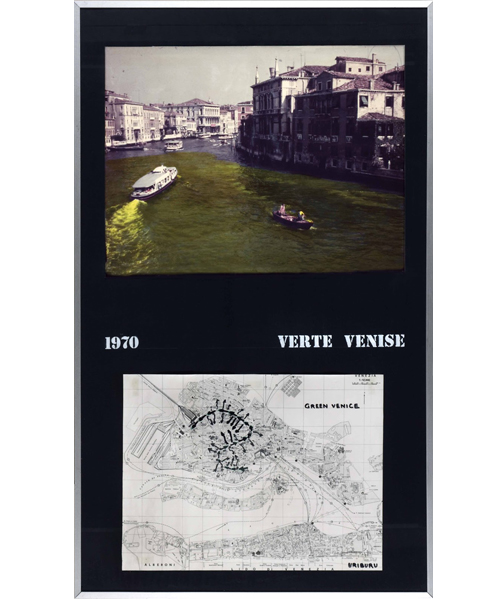

In this edition, we present “Points of View”, an activity inspired by Manifiesto verde [Green Manifesto], the Museo Moderno’s exhibition in which works by artist and pioneering activist Nicolás García Uriburu (Argentina, 1937–2016) are shown in dialogue with numerous pieces by other artists. The works show nature as a living entity, made up of an endless number of interconnected beings, in which everything flows and is integrated, absorbed and transformed.

The show celebrates painting and the imagination as essential means through which we can recognise the vigour that characterises our planet. To represent water, soil, flora and fauna, an authenticity is needed that cannot be achieved simply by copying, but instead requires the artist to relate to the dreamlike materials and environments that surround them during their process of search and investigation.

Let’s get to work!

For this activity, make use of coloured pencils, crayons, chalk pastels or even watercolours, and feel free to work on any type of drawing paper you like.

Find your inspiration in the works of art included in the exhibition: works by the likes of Nora Correas, Florencia Böhtlingk and Nicolás García Uriburu. Look for pieces in which nature is represented from different imaginative points of view and, from there, create your own unusual landscapes.

The first step is to imagine changing the scale between your own body and that of the environment. Imagine shrinking to the size of a mouse, or even a mosquito! Or growing to be as tall as a larch.

Next, imagine walking through nature at that new size and observing the surrounding diversity. What would the grass look like from the point of view of an ant? And what about from the point of view of a hare, a butterfly or a pigeon? What types of things might one see from up above or down below? What might a tadpole swimming in a marsh see? Or a dolphin surfacing in the ocean to breathe? What might one see from the top of a palm tree in the jungle of Misiones?

When you return from your imaginary excursion, draw the landscape you pictured on the paper and share it with the rest of your group.

We would love to see images of your creations! You can send them to us at: [email protected]

We hope you can visit the museum to see these and other works included in the Manifiesto verde [Green Manifesto] exhibition.

What the Stars Have to Say

Proposals for Classroom Project

The exhibition A 18 minutos del Sol [18 Minutes from the Sun] opened at the museum in August and it centres around astronomical observation and access to outer space, creating a dialogue between artistic imagination and scientific exploration.

As part of the exhibition, Pauline Fondevila – a French-born artist who resides in Córdoba – has created a large-scale mural in the hallway that leads to the gallery spaces. The piece brings together elements from other works in the exhibition and has them interact with imagined beings from outer space and fragments of song lyrics.

For today’s activity, you will need a piece of black paper, white acrylic or tempera paints, a brush and a light-coloured pencil.

– Begin by thinning the acrylic or tempera paint until it reaches a fluid consistency.

– Wet your brush and load it with the paint.

– Then, hold it over the black paper at a height of approximately 20 cm and, tapping the handle of the brush gently, let small droplets of paint fall onto the paper.

– After covering the black paper with dots of paint, let it dry.

– Once dry, take your light-coloured pencil and join some of the dots together. By doing so, you will begin to create an outline for a constellation. Is it a recognisable object? What is it? What features does it have?

The constellation may be, for example, a cross that could help travellers to navigate. Or it might be a mythical being that is part of a community’s history.

Once you have finished your drawings, share them with the group to find similarities. Reflect on your work together.

We would love to receive pictures of your creations! You can send them to us at: [email protected]

Be sure to visit the exhibition A 18 minutos del Sol [18 Minutes from the Sun], Wednesdays to Mondays from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

Image of the first floor hallways of the Museo Moderno, where a large-scale mural has been painted directly onto the wall. It consists of a large black background on which stars, planets, writing and other graphic elements have been painted in lighter colours.

Offerings

Proposals for projects in the classroom

Every August, the indigenous cultures of the Andes celebrate festivals and rituals in honour of the Pachamama, or Mother Earth. For example, on the first of the month, an offering is made to her in the way of food or beverages that are introduced by means of a hole or “mouth” in the earth, giving these items back to her in thanks for everything she has given to us.

Delcy Morelos’ monumental work El lugar del alma [The Place of the Soul] is currently on view at the Museo Moderno. It evokes the rituals that take place in different locations of the Americas to give thanks to the Pachamama. The work is an installation made of earth that has been specially prepared with mixes of cinnamon, cloves and coffee. The show transforms the gallery space, allowing visitors to walk through the piece from different directions, in contemplation and reflection,.

We propose that you reflect on the thanks you have to give, draw representations of these and then sharing them in a group. First, think of gratitude as something that nourishes and gives us strength. Next, for each of the thanks you would like to express, decide which food or object could serve as a symbol for it. For example, could a bunch of grapes represent union and friendship, and our gratitude for it? Or could a particular sweet recall the love of our grandparents? After taking the time to reflect, use coloured pencils and paper to draw the offerings you imagined. Once finished with the drawings, share them with the group to find similarities and reflect on them together.

We would love to receive pictures of your creations! You can send them to us at: [email protected]

Image of the exhibition Delcy Morelos El lugar del alma, with a detail of the earth combined with cinnamon, cloves and coffee that was used to construct the work.

Colour fields

Proposals to Create at Home

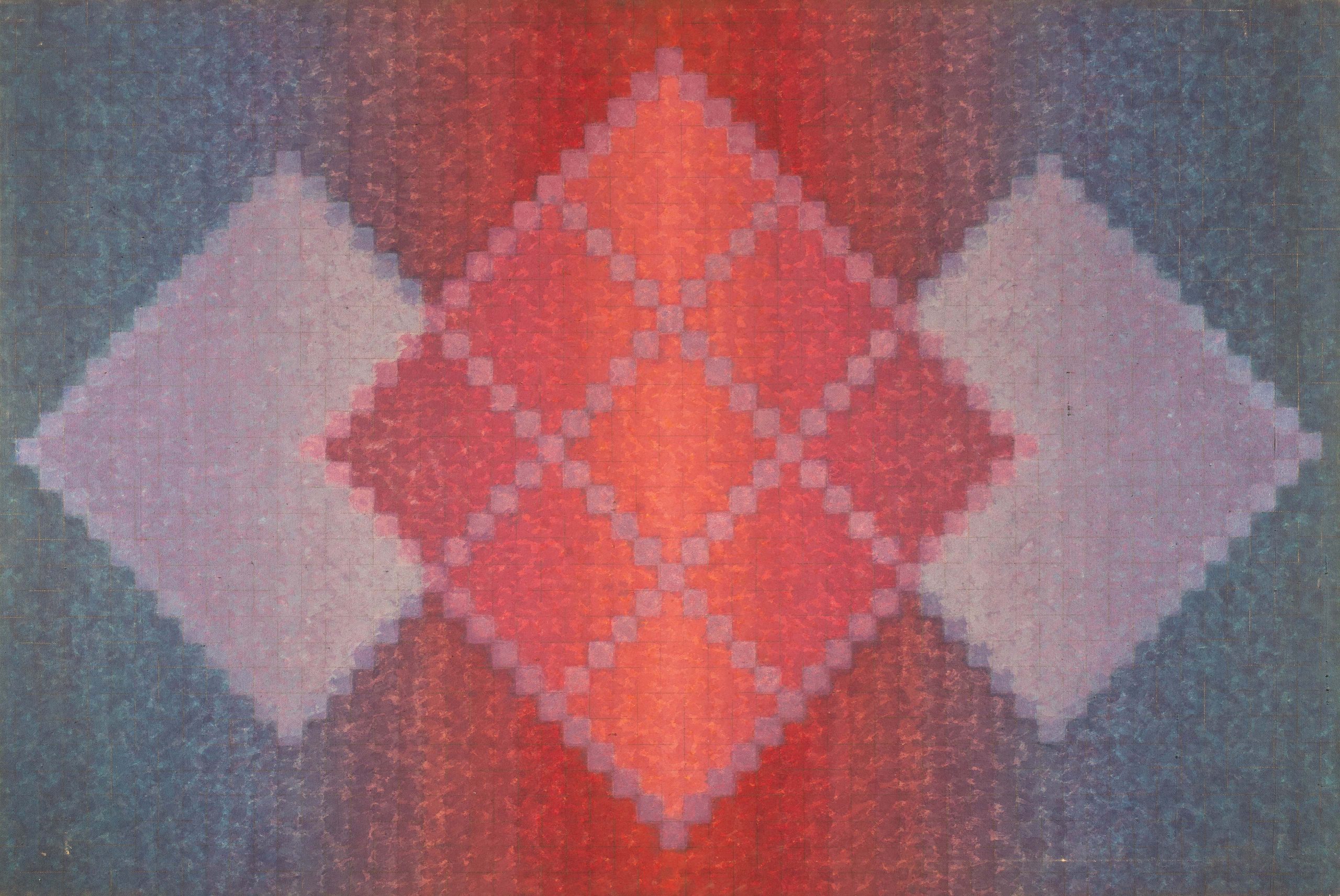

María Martorell (1909-2010) was an artist from Salta and a pioneer of abstract painting in her home province. She played with the laws of vision to create large compositions of geometric figures that allowed her to produce the sensation of space. Although Martorell’s works do not have recognisable figures, many of the shapes and colours of her paintings are reminiscent of the landscapes of north western Argentina.

Several works by the artist can be found in the permanent collection of the Museo Moderno, including Ekho C.

Let’s get to work!

Together with your family or friends, draw illustrated postcards of different landscapes you may have visited while on holiday in Martorell’s style!

First, choose a landscape you wish to transform into an abstract postcard. It may be a natural landscape, such as a seascape horizon, a river view with rocks and plants, or perhaps the rolling silhouette of some hills or mountains. Or you could choose to depict an urban landscape, or the garden of a family member’s house you have visited, or a view of the city from out your window. You could work from a photo or, if drawing from memory, make a sketch to begin with. The most important thing when translating these landscapes into an abstract postcard is to pay attention to all of the recognisable objects and shapes so as to transform them into lines and colours.

Draw your abstract landscape on a sheet of paper the size of a postcard, 10 x 15 cm. First, look at your photo or sketch and select the three main colours you see in your chosen landscape. Are they the colours of the sky, the water, or the treetops? Or perhaps they are the roofs of buildings or the flowers in a flowerpot?

Take coloured pencils or markers in the three different colours you have chosen and wrap them together using an elastic band, lining them up so the tips are all at the same height.

You are now ready to draw an abstract postcard! First take all of the elements of your landscape and transform them into lines and shapes. Start by looking at the lines of your landscape and discerning the directions they travel in. Are there more horizontal lines? Are there straight lines or curved ones? Do they stretch across the entire landscape, or are they concentrated in one spot? Draw the lines using your markers or coloured pencils; since they are gathered together in the elastic band, the result will be three parallel lines made with a single gesture.

Using different colours, you can add details or colour in the geometric spaces between the lines you drew on the card.

To finish, write the name of the place you have depicted and a message to a loved one on the back of your postcard Give it to them as a present the next time you see each other!

We would love to see images of your creations! You can send them to us at: [email protected]

We look forward to seeing you at the Museo Moderno, where you can see the works of María Martorell.

María Martorell. Ekho C, 1968, Acrylic on canvas, 180 × 320 cm. Collection of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Everyday Impressions

Proposals to Create at Home

Argentine artist Eduardo Basualdo creates installations, sculptures, objects and drawings. Pupila [Pupil] is the solo exhibition he created especially for the Museo Moderno, in which he mixes all of these artistic languages and uses drawing as a trigger to invite us to explore human fantasies.

At the centre of the exhibition gallery is a large installation that was created using black aluminium foil, which is a very malleable type of paper covered with black matte paint on both sides and is used in theatre and cinema to block and control the light.

In this edition of Proposals to Create at Home, we invite you to find inspiration in Eduardo Basualdo’s Pupila installation and explore volumes in space, which they can then translate into drawings.

To begin, you are going to need a sheet of aluminium foil, like the ones used in the kitchen. First, go around your house looking for interesting shapes and textures that you could use as a mould to give shape to your sheet of aluminium. Cover the objects with the foil, pressing it lightly so that it takes on the shapes, leaving their mark on the sheet. Cover the entire surface with aluminium until you create a small sculpture in relief of your chosen object.

Now look closely and compare the shapes of the sculpture you created. Look at the differences that emerge when viewed from different angles. Do you think you can create a drawing of the sculpture, with its volumes and voids? Can you also imagine those voids as shapes?

We would love to see images of your creations! You can send them to us at: [email protected]

We hope you can visit the museum to see the works in the exhibition Eduardo Basualdo: Pupila.

Photos of the Eduardo Basualdo: Pupila exhibition Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 2022

Sketches for a world in movement

Proposals for projects in the classroom

Mónica Girón is an Argentinian artist who investigates local and global geography to reflect on the connections between art and life. The artist is particularly interested in the corporeality of the continents, the movement of land masses and the circulation of energy in the seas through ocean currents. She also explores the movement of humans through space and uses different materials to create works related to the harmonious co-existence between people, flora, fauna and territory.

The Museo Moderno’s anthological exhibition, Mónica Girón: Enlaces Querandí [Mónica Giron: Querandí Connections] includes both new projects by the artist as well as some of her earlier works. Inspired by the exhibition, we have come up with an activity that asks students to observe nature and then create their own abstract drawings.

Look at different images where there is a repeating pattern that suggests movement. These could be pictures of the ocean, of clouds, or perhaps of a forest. Or they could be aerial views of cities or the countryside. Perhaps you can use images showing animal migrations or human population movements throughout history. Based on these images, see how you respond to the following questions:

Is it possible to translate the shapes and movements that appear in the images into lines? For example, how would you draw the movements of currents around the planet, or the effect of a gust of wind through some plants? How would you draw the migratory routes of a species of bird? What differences can you find between all of these different types of movement?

If we think about how humans inhabit the spaces in which we live, do you think it is possible to translate all of those patterns and movements we make as we go about our daily lives in our home, neighbourhood or city into a drawing? Can you make a drawing that represents the journey of your ancestors through different cities, countries or continents? Try to see if you can draw their journeys. What words could you add to the drawing to make it more personal?

To trace their journeys and turn them into a drawing, make use of coloured pencils, crayons, chalk pastels or even watercolours. Use any type of drawing paper you like to create your work.

We would love to see images of your creations! You can send them to us at: [email protected]

We hope you can visit the museum to see these works and all of the others that are included in the exhibition Mónica Girón: Enlaces Querandí [Mónica Girón: Querandí Connections]

Photos of the exhibition Mónica Girón: Enlaces Querandí [Mónica Girón: Querandí Connections] Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 2022.

Outstanding posters

Proposals for classroom projects

The Museo Moderno has a large collection of graphic and industrial design pieces, some of which date back to the 1960s and 1970s, when artists such as Edgardo Giménez, Oscar Smoje and Guillermo González Ruiz became interested in the language of mass media and advertising, incorporating them into their own artwork. Using posters as supports and printing techniques such as engraving, they explored the possibilities of serialization, not only as a means to promote themselves, but also to be able to reach a much wider audience than the public that typically participates in the art world.

Several posters created by the artists during these investigations are featured in our current exhibition, Cuerpos contacto [Contact Bodies].

As a classroom project, we suggest you create a poster that combines text and images. Working in groups, select a movie, play, television series, animé or concert you enjoyed. You could also choose an event that will take place at your school. Next, have a brainstorming session and note down those elements that characterize the work you have chosen. Select some images and choose the font or style of typography you wish to use. Then, using different materials and techniques such as collage, drawing, or transfers, compose your poster, paying attention to the spaces you dedicate to text and images. What is the most important message your poster should convey? Should it have a title, include an important date, people or characters? And, finally, who is your poster’s target audience? Who should read it? What is the best place to position it so that it can be read? Make copies of your poster and hang them in different places!

We would love to receive pictures of your creations! You can send them to us at: [email protected]

We hope you can visit the museum to see these works and all of the others that are included in the Cuerpos contacto exhibition.

Oscar Smoje, Pomelo [Grapefruit], 1970, and Oscar Smoje, The Explosion, 1972.

From the discard pile to an ornament

Proposals for classroom projects

Mi Gaudí trucho [My Fake Gaudí] is an installation by renowned Argentinian artist, designer, photographer and décorateur Sergio De Loof (1962-2020), and it is currently on show as part of the Cuerpos contacto [Contact Bodies] exhibition. The installation was also part of the anthological exhibition ¿Sentiste hablar de mí? [Never Heard of Me?] which took place at the museum between 2019 and 2021, and which celebrated the imprint and legacy of this artist and emblematic figure of the Buenos Aires underworld.

To create the work, De Loof recovered everyday objects that were in disuse or discarded and gave them a new meaning by turning them into ornaments for a doorway. He took pieces as diverse as bottle caps, sweet wrappers, toys and tiles and created an ornate portal which, due to the enormous number of elements and overlapping colours, in some way recalls the modernist works of the Catalan artists Antonio Gaudí, such as Parque Güell or Casa Batlló.

The aesthetic reattribution of the meaning of these discarded objects was a key element of Sergio De Loof’s artistic programme, in which he played with the distances that separate luxury from poverty, and the aristocratic palate from popular taste.

We suggest you create an object in which you give every day discarded elements a new meaning. Can a magazine be turned into an item of clothing? Can jewellery be created from broken or discarded toys? Can a decorative pattern be made out of sweet wrappers?

We would love to receive pictures of your creations! You can send them to us at: [email protected]

Sergio De Loof, Mi Gaudí trucho [My Fake Gaudí], 2019. Broken tiles, second-hand objects and

rubbish. Collection of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires. Donated by the De Loof

family, 2020.

Abstract tradition

Proposals for projects in the classroom

Mancapa is a painting by Alejandro Puente that is part of the exhibition Vida abstracta [Life in the Abstract].

In this period of his career, Puente’s approach to abstraction sought to recover patterns from pre-Columbian art. For that reason, we propose that you first seek out different traditional designs of the communities of Argentina. Are there visual elements in those works that are similar to the ones that appear in this painting? What elements are similar? Which materials or objects were used by the different cultures of the indigenous peoples of Argentina for their designs? What were the functions of these objects? Does Puente’s painting fulfil the same function?

The geometric designs found in the art of indigenous peoples often are symbols that allude to elements that were significant to these cultures. We propose that you design a symbol that speaks to you or represents you and apply it to a coat of arms, a flag, or your school uniform. Pay attention to the shapes and colour palette that you select for the composition of the symbol. What would you like the symbol to represent, and how can you materialize that idea? What colours can you use to transmit the idea more clearly?

We would love to receive the creations of your students!

You can send images of them to [email protected]

Alejandro Puente, Mancapa, 1979

Transforming spaces

Proposals for projects in the classroom

Árbol de cuadros [Tree of Paintings] is a performance and audio-visual work by Magdalena Jitrik that is part of the exhibition, Vida abstracta [Life in the Abstract]. The video, filmed in Super 8, shows different trees the artist has used as a support to hang her paintings. In this way, she transforms an everyday space (in this case, a part of nature) into an exhibition space and the paintings, instead of being enclosed by four walls, are linked to the environment around them.

We suggest that you showcase the works of your students in an unusual space. You can walk around your school, identifying possible locations that would attract the attention of the group. After choosing a space, arrange the works and then observe the result. Does hanging the works in the space change how the works appear compared to how they looked when they were inside the student work folders, or hung in the classroom? Does the space in which the works were hung look different? Has there been a change in the way the school community moves through the space where the works are hung?

We look forward to seeing you at the museum so that you can visit this and all of the works of the Vida abstracta [Life in the Abstract] exhibition. We would love to see the creations of your students! You can send images of them to [email protected]

Magdalena Jitrik, El fin, el principio [The End, the Beginning], 2012-2013. Super 8 video transferred to digital media 10 m, 15 sec.

Bodies on Display

Proposals for projects in the classroom

Fragmentos [Fragments] is a work by Mariela Scafati that is part of the exhibition Vida abstracta [Life in the Abstract]. The work plays with colour and is constructed of fabric and plain colour frames which are arranged in such a way as to form a figure that resembles a human body.

Our proposal is to create a collective work that reconstructs a body through juxtaposing planes of the same colour. The planes could consist of hand-painted papers or a selection of everyday objects of different sizes, such as clothing, books, folders, photographs, plastic bottle caps, and other elements consistent with the chosen colour.

Once the work is completed, think about the following questions: In terms of the body you created, what do the created forms convey? What about the colour that was chosen, what does it communicate? What do colours communicate when they are applied to a human body? Is it the same to represent a body using orange, rather than blue, red, white, or black?

We look forward to seeing you at the museum so that you can visit this and all of the works that make up the Vida abstracta [Life in the Abstract] exhibition. We would love to see the creations of your students! You can send images of them to [email protected]

Mariela Scafati, Fragmentos antes de tocar la guitarra [Fragments before playing the guitar], 2015

Descubrir nuestro entorno

Propuestas para trabajar en el aula

Febrero es el mes del regreso a clase, por lo que compartimos con los docentes algunas ideas para trabajar en el aula la representación del territorio a partir de las artistas de la exhibición Adriana Bustos, Claudia del Río, Mónica Millán: Paisaje peregrino. Hoy: Claudia del Río.

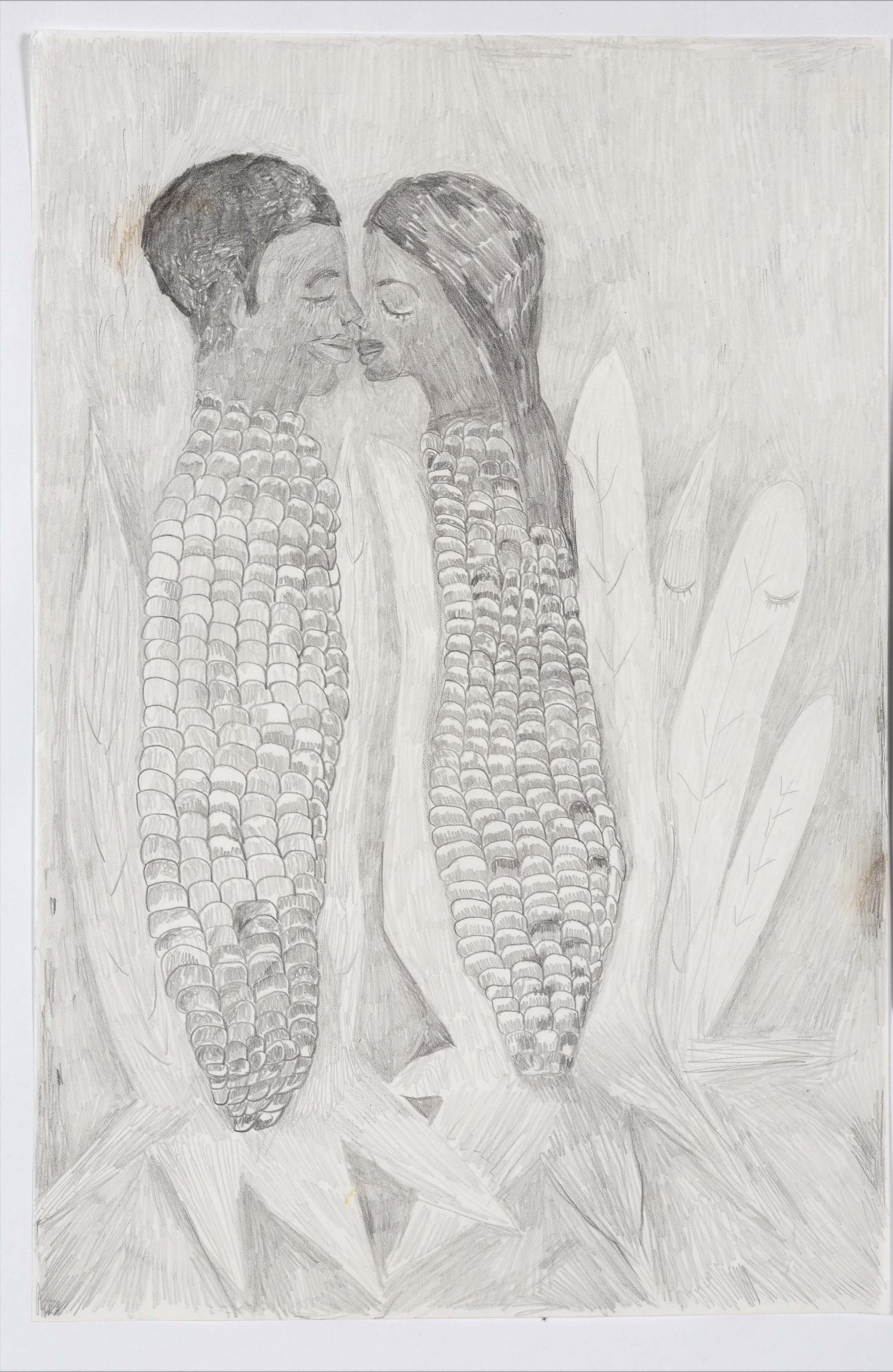

Claudia del Río (Rosario, 1957) tiene una extensa serie de dibujos a los que llama los “niños maíces”: a través de ellos genera seres que mezclan los rasgos humanos con uno de los alimentos centrales de Latinoamérica. Así, deja al descubierto que gran parte de lo que somos se vincula con nuestro entorno: el clima en el que vivimos, los animales que conviven con nosotros, la tierra que nos rodea y aquello que obtenemos de ella para vivir. Encontrarnos con imágenes que mezclan estos elementos en una misma figura nos invita a pensar en nuestros propios consumos y en nuestra relación con el entorno.

Les proponemos imaginar con qué elementos de nuestro entorno nos encontramos más mimetizados: ¿hay algún alimento propio de nuestro lugar de origen con el que nos sentimos especialmente conectados? Y si no, ¿hay algún alimento propio de otro lugar con el que sintamos esa relación? ¿Hay algún otro elemento, natural o artificial, al que nos sintamos profundamente ligados? Invitamos a realizar un retrato en el que se mezclen nuestros rasgos personales con los de ese alimento u objeto.

Niños Maíces, Claudia del Río, 2016. Foto: Viviana Gil

Construir paisajes

Propuestas para trabajar en el aula

Febrero es el mes del regreso a clase, por lo que compartimos con los docentes algunas ideas para trabajar en el aula la representación del territorio a partir de las artistas de la exhibición Adriana Bustos, Claudia del Río, Mónica Millán: Paisaje peregrino. Hoy: Adriana Bustos.

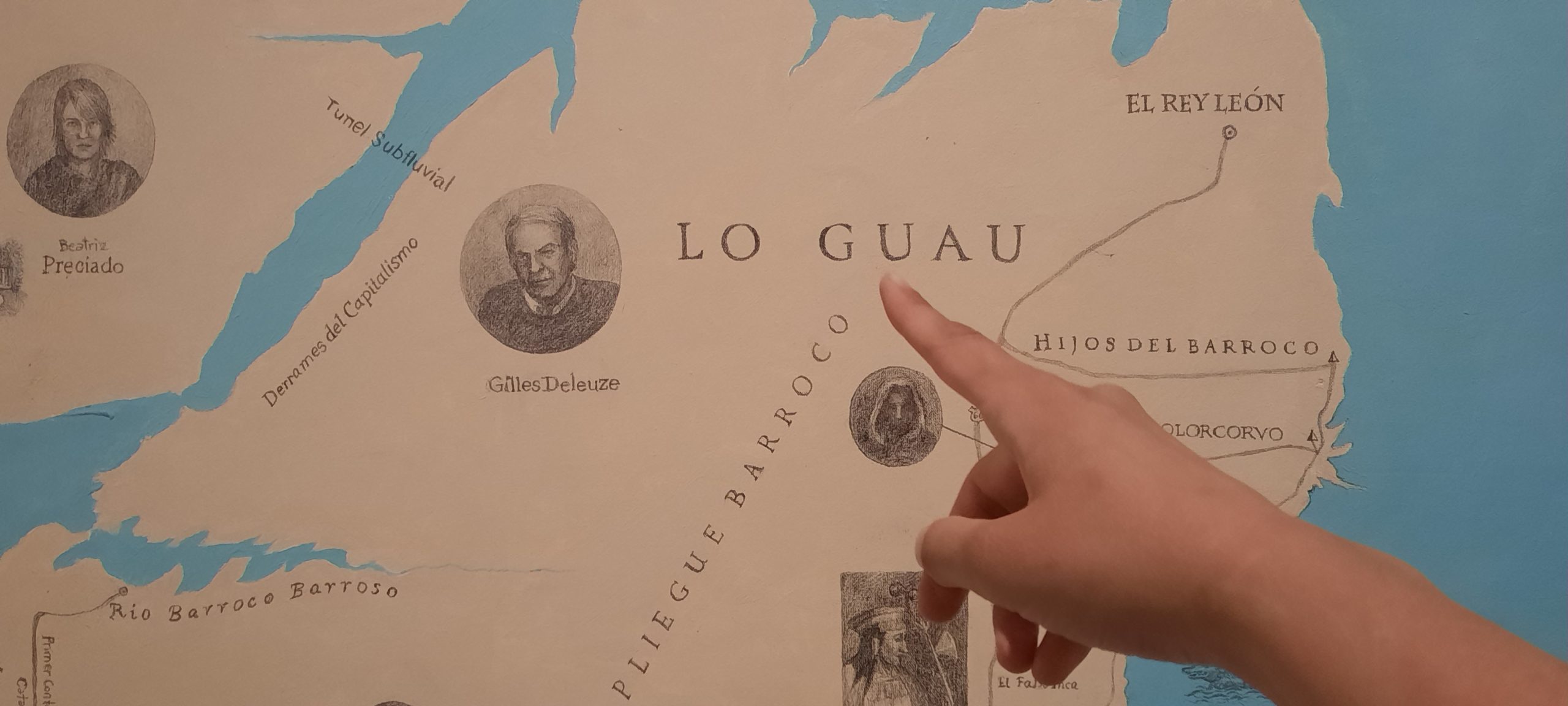

Adriana Bustos (Bahía Blanca, 1965) trabaja de manera recurrente con los mapas. En sus obras traza cartografías personales que se mezclan con los mapas convencionales: arma continentes y océanos imaginarios, incorpora personajes ficticios y reales, muchos de ellos históricos. Estos mapas, tan propios y atravesados por sus intereses, nos invitan a pensar en la arbitrariedad de los mapas que nos rodean todos los días ¿Quiénes han determinado nuestros mapas a lo largo de la historia? ¿Qué representan esos mapas y para qué sirven? ¿Qué información incluyen y cuál dejan afuera? ¿En qué se parecen a un paisaje y en qué se diferencian?

Proponemos trabajar en el diseño de un mapa personal, que represente el lugar donde cada uno vive. Ese lugar puede ser la habitación de una casa, un barrio, una ciudad, un país. Puede incluir animales, elementos geográficos así como otros personales, puede tener fronteras delimitadas o estar abierto a todo aquello que lo rodea. Lo importante es recordar que, por más que sea imaginario, un mapa siempre es una guía para ayudar a quien lo lee a conocer, entender y cuidar un entorno. Invitamos a los estudiantes a pensar: ¿Qué entenderá sobre mí quien lea este mapa?

Imago Mundi XI: Wheel Map, Adriana Bustos, 2012

Febrero es el mes del regreso a clase, por lo que compartimos con los docentes algunas ideas para trabajar en el aula la representación del territorio a partir de las artistas de la exhibición Adriana Bustos, Claudia del Río, Mónica Millán: Paisaje peregrino. Hoy: Adriana Bustos.

Adriana Bustos (Bahía Blanca, 1965) trabaja de manera recurrente con los mapas. En sus obras traza cartografías personales que se mezclan con los mapas convencionales: arma continentes y océanos imaginarios, incorpora personajes ficticios y reales, muchos de ellos históricos. Estos mapas, tan propios y atravesados por sus intereses, nos invitan a pensar en la arbitrariedad de los mapas que nos rodean todos los días ¿Quiénes han determinado nuestros mapas a lo largo de la historia? ¿Qué representan esos mapas y para qué sirven? ¿Qué información incluyen y cuál dejan afuera? ¿En qué se parecen a un paisaje y en qué se diferencian?

Proponemos trabajar en el diseño de un mapa personal, que represente el lugar donde cada uno vive. Ese lugar puede ser la habitación de una casa, un barrio, una ciudad, un país. Puede incluir animales, elementos geográficos así como otros personales, puede tener fronteras delimitadas o estar abierto a todo aquello que lo rodea. Lo importante es recordar que, por más que sea imaginario, un mapa siempre es una guía para ayudar a quien lo lee a conocer, entender y cuidar un entorno. Invitamos a los estudiantes a pensar: ¿Qué entenderá sobre mí quien lea este mapa?

Imago Mundi XI: Wheel Map, Adriana Bustos, 2012

Alberto Greco formó parte del Movimiento Informalista, una corriente artística que propuso nuevas maneras de pensar el arte y puso en discusión el límite de lo ¨artísticamente correcto¨ a partir de la exploración de una nueva materialidad en la pintura.

Sus series de pinturas negras, realizadas a partir de 1959, son telas y maderas en las que mezcla el óleo con brea, esmalte, tierra y todo tipo de materiales no tradicionales. Exponía muchas de sus obras a la intemperie, para que las fuerzas de la naturaleza, como la lluvia, el viento, el rocío del amanecer o el calor del sol del mediodía, alteraran azarosamente la composición y los materiales, lo que daba lugar a resultados imprevisibles y maravillosos.

¿Te animás a trabajar este proceso en una obra de tu autoría?

Alberto Greco. Sin título o Pintura hombre, Óleo y esmalte industrial sobre tela (1960). Exhibida en ¨Una llamarada pertinaz. La intrépida marcha de la colección del Moderno¨, en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires (2018)

La formación académica de los artistas no se limita únicamente a las artes visuales. El cruce entre la práctica artística y otros campos del conocimiento da lugar a otras dinámicas que enriquecen y generan nuevos puntos de vista acerca del arte. Desde el área de universidades del museo te compartimos el caso de Elda Cerrato (argentina nacida en Asti, Italia, en 1930).

En el segundo subsuelo del Museo de Arte Moderno tiene lugar la exhibición temporaria “El día Maravilloso de los Pueblos”, de Elda Cerrato.La exposición antológica recorre diferentes momentos de su vasta producción artística. La artista se formó como bioquímica y, en su etapa inicial, se puede apreciar el cruce entre sus estudios en bioquímica y las experimentaciones plásticas y el esoterismo. La serie “Ser Beta” aborda el misterio de los seres vivos, los planetas y el espacio exterior, y representa la visión de la artista sobre la vida, sus formas y sus energías.

Elda Cerrato, Algunos segmentos, 1970, film 16 mm transferido a digital, color, sonido. Colección del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires.

Durante gran parte del 2020 sentimos que estábamos inmersos y éramos seres imposibles dentro un film de ciencia ficción. La frontera entre lo inverosímil y lo real estuvo sutilmente desdibujada. Desde el Museo Moderno los invitamos a reflexionar sobre esta obra de nuestra colección.

Sebastian Gordin (1969, Buenos Aires) utilizó poliéster, fibra de vidrio y madera para darle vida a esta obra titulada “Nikita G” realizada en el año 2004. En ella observamos una realidad alternativa con seres humanoides en un escenario fantástico de destrucción.

Es una pieza intrigante que nos hace pensar en las diferentes formas que puede adoptar el caos dentro de la cabeza de un artista… Pero también nos invita a considerar los posibles escenarios virtuales o materiales que construimos colectivamente y el rol individual que cada uno tiene en la construcción de nuestra cotidianeidad.

Sebastián Gordin, Nikita G, 2004 exhibida en Una llamarada pertinaz, la intrépida marcha de la colección del Moderno en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires (2018)

¿Cómo se nombra una obra de arte?

A través de los títulos, los artistas ofrecen claves para comprender sus obras de arte. Pueden ser irónicos, narrativos, poéticos o explicativos. A veces, conocer el título de una obra puede cambiar lo que pensamos sobre ella. En 1962, Emilio Renart compuso esta obra con un lienzo que se cuelga de la pared y una estructura metálica hecha de aluminio, tul, aserrín y resina que emerge de la pintura. En aquel entonces, mucha gente consideró que esa y otras piezas similares del artista eran “monstruos”. En algunas visitas guiadas, chicos de varias escuelas le pusieron nombres como “escultura viva”, “gallina galáctica” o “submarino cósmico”. Renart le puso Bio-Cosmos nº1. ¿Cómo le pondrías vos?

Emilio Renart, Bio-Cosmos nº1, 1962, estructura metálica, aluminio, lienzo, pintura, cola vinílica, tul, aserrín, resina poliéster, 230 × 300 × 90 cm. Adquisición 1968. Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Luis Felipe Noé (Buenos Aires, 1933) investiga, desde hace más de medio siglo, la teoría del caos. El artista argentino, en lugar de rechazar el desorden, lo abraza. En su libro Antiestética (1965) acepta y reconoce el caos como una nueva realidad, necesaria para el funcionamiento de un mundo en constante cambio. Y agrega que, como habitantes latinoamericanos que somos, el caos es algo estructural con lo que tenemos que aprender a convivir.

Desde el Museo de Arte Moderno queremos invitarlos a seguir ampliando y reflexionando sobre lo que entendemos por caos. La experiencia de la pandemia mundial por Covid-19 nos hizo sentir, en muchos casos, en un abismo, en una realidad distópica y desesperante, pero también la cuarentena nos ha posibilitado espacios de introspección y crecimiento interior.

En esta línea de pensamiento, ¿cómo impactó el caos del contexto actual tu experiencia universitaria? Te invitamos a conocer más sobre la teoría de Luis Felipe Noé y a que nos dejes en los comentarios tu propia visión sobre el caos, ¡nos encantará leerla!

Luis Felipe Noé, Figuras, 1960, óleo sobre tela. Colección del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires.

Esta es una de las obras del artista Nicolás García Uriburu de la colección del museo. Después de la observación, proponemos el siguiente desafío: investigar sobre esta experiencia artística y trazar relaciones que nos permitan reflexionar sobre el presente.

¿De que se trató la obra?

Investiguen sobre el contexto en el que se produjo.

¿Cómo discute la obra con ese contexto?

En relación a las respuestas que hayan surgido entre todos, les sugerimos conectar su relación con el presente.

Nicolás Garcia Uriburu, Verte Venecia, 1970, 101 x 60,5 cm, fotografía coloreada y mapa Colección del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires (donación del artista), 1980