Art has always had the capacity to transform materials and objects into pieces destined for admiration, study and contemplation. Alberto Greco was an artist who abandoned that tradition and opened a new space dedicated to the observation of reality through the use of marks, signs and signalling. In this way, he extended the disciplinary limits of art as well as art itself. The opening of his first major exhibition produced in Argentina, Alberto Greco ¡Qué grande sos! [Alberto Greco, How Great You Are!], invites us to once again embark on the adventure of a live art.

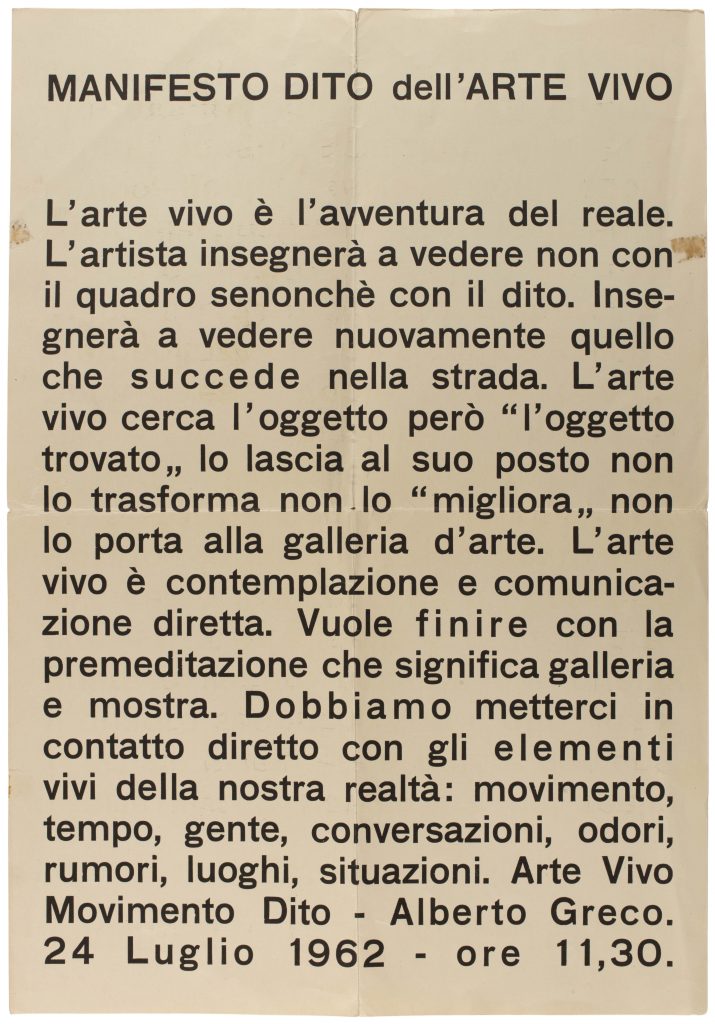

In April, the Museo Moderno invites you to participate in La aventura de lo real [The Adventure of the Real] and bring to life the opening words of Greco’s ‘Manifesto Vivo-Dito del Arte-Vivo’ [Vivo-Dito Manifesto], with which he papered the streets of Rome in 1962: “Live art is the adventure of reality. The artist will teach you to see not with the frame, but with the finger. He will teach you to once again see what is happening in the street.” Vivo-dito (vivo is the Italian for living and dito, for finger) is the action of pointing, enclosing in a chalk circle or signing objects, people or situations of everyday life, transforming them into ephemeral and spontaneous works of art. Greco proposed taking our surroundings as an artistic experience that renews our relationship with the world. This serves as a reminder that culture is never a completely transparent, stable or settled concept, but a changing and shifting one.

Working from this rationale, Greco’s signs transform what was understood by art and expand through concrete actions that the Museum intends to deploy in all their different dimensions. We have called upon a group of artists to recover vivo-dito as a radical gesture to single out the happenings of today: the contemporary features of everyday life, the pulse of different cities across the country, the familiar objects that surround us. Vivo-dito is always a contemporary action and it ignites with the power of our present moment. It is this premise that spurs us to extend the invitation to our community to adopt the use of this signalling, to make their photographs, videos, voices and gestures, thus creating a chorus of images showing the complexity of the present.

While this call goes out from #MuseoModernoEnCasa, through our different social media platforms, we propose another action to bring us together through writing, tracing, gestures and drawing. The Department of Education of the Museo Moderno invites you to recreate Greco’s Manifesto Vivo-Dito del Arte-Vivo [Vivo-Dito Art Manifesto-Scroll], which he produced in Piedralaves (Spain), on a roll of paper 300 metres long by 10 centimetres wide. This scroll of paper was the container of the signatures, drawings, collages and writings of the community of that town – mainly of the children who came to leave their mark –thus bringing to life a sort of exquisitely graphic corpse. We will put a new scroll into circulation so that different communities across the city and the country can take part, and we will subsequently exhibit the results of this collective action.

The prospect of considering writing as an infinite line, as a texture on paper or even as an anonymous carving on furniture resonates in the works of Ulises Mazzucca, presented in the exhibition Gimnasia espiritual [Spiritual Gymnastics]. In his ouvre, a biography is a drawing, writing is a calligram and words are the expression of anonymous urban life. So, is writing, ultimately, a kind of gymnastics? In this exercise, as in Greco’s work, the relationship between writing and biography is primarily articulated through experience, the source of a calligraphy that is at once intimate, collective and relational.

Following this direction and allowing ourselves to be carried along with it, the expansive and infectious gaze proposed by Greco also unfolds throughout the museum; there are resonances, echoes and signs of it in the artworks and exhibitions that can be visited in the different spaces of the museum. The works of Cotelito’s Vuelvo como un jardín después del invierno [I Return Like a Garden After the Winter] and Diana Aisenberg’s Mística robótica en la economía de cristal Mystical Robotics in the Crystal Economy] transform architecture and spaces through painting or the accumulation of objects. From this perspective, Nicanor Aráoz’ large-scale installation made especially for his exhibition Sueño sólido [Solid Sleep] conceptualizes the room as a territory that rekindles concern for human beings’ sensitivity in view of the brutal reality of the present. It points out the tensions and dissolutions between the real and the virtual, between nature and human actions as a declaration of a compromise with the present. A concrete manifestation of this compromise is the interest in partying (in the exhibition, a jukebox randomly plays vintage music). Festivities, then, are a ritual in which a community event is held wherein art manifests itself more as a way of engaging the world than as an attempt to provide answers.

Elian Chali’s Plano inesperado [Unexpected Plane] also functions along the same lines; in his intervention on the façade of the museum, he presents an elastic geometry that is capable of blurring the limits between the interior (the museum) and the exterior (the city). The artist considers his gestures to be like the points of an urban acupuncture treatment that tries to alleviate the pain so that the city can appear in all its splendour, reactivating circulation and sparking movement. If the aforementioned artworks approach their capacity to transform contexts and spaces through permeability, the opposite is true of Elda Cerrato’s work, which is presented in El día maravilloso de los pueblos [The People’s Wonderful Day]. Here, zones are delineated using geometric shapes, maps and crowds that point out precise realities and reveal to us both the specific Latin American context, as well as other planes that exceed material reality. These works, together with the actions Greco proposed, are an invitation to a permanent agitation of the senses that encourages an attentive contact with the everyday: movement, people, time, places, smells, conversations, situations. It is an impulse that makes art a way of teaching us to see again, to perceive the real as the true adventure.

In the coming weeks we will present a grand tour of the exhibition Alberto Greco: ¡Qué grande sos! [Alberto Greco, How Great You Are!]. In this tour, we will pause to consider those elements and activities that are almost invisible to museum visitors, but which constitute the basic framework for the presentation of the works, documents, materials and texts required to bring every exhibition to life. Each chapter recounts stories from the different areas of the museum that worked to create the exhibition. Each space, artwork and material exhibited represents the work of many people. This strong synergistic relationship includes not only the different areas of the Museo Moderno – such as Curatorship, Collections and Conservation, Production and Installation, Publications and Education Departments – but also essential external actors, such as guest artists, the collectors and institutions that lend works, carriers, interior painters, framers, photographic printers, silkscreen printers and printers, among others. By sharing with you the voices and experiences of these people, we can highlight the number of people and the knowledge that goes into producing a retrospective exhibition of a historical artist like Alberto Greco. #GrecoExpanded

Museo Moderno en Casa [Museo Moderno at Home] revives one of artist Alberto Greco’s most radical gestures: the vivo-dito. These were ephemeral and spontaneous works of art in which he pointed with his finger, enclosed with a chalk circle or signed objects, people or situations of everyday life. His publication of the Manifesto Arte Vivo Movimiento Dito [Manifesto of the Live Art] papered the streets of Rome on July 24, 1962. In that text he declared:

“Live art is the adventure of the real. The artist will teach you to see not with the frame, but with the finger. He will teach you to once again see what is happening in the street. Living art looks for the object, but the found object is left in its place, it is not transformed, it is not improved, it is not taken to an art gallery. Living art is contemplation and direct communication. It wants to put an end to premeditation, which means galleries and exhibitions. We must get in touch with the living elements of our reality. Movement, time, people, conversations, smells, rumors, places and situations.”

Understanding that vivo-dito is always a contemporary action and is ignited by the power of the present moment, the Museo Moderno invited a group of artists to point out, outline or signal the happenings of today: the contemporary marks or features of everyday life, the pulse of different cities across the country, the objects that surround us.

With these actions, Alberto Greco’s work continues to expand and gain new meanings. The proposals of these artists show us different ways of reformulating vivo-dito. The city is most conducive to carrying out such actions, whether through an intervention or through collecting what is happening in the streets. At the same time, the Museum emerges as a space for signalling art and a place that makes these encounters possible.

Alberto Greco, Manifesto ditto dell’arte vivo, 1962, letterpress printing, 50 x 34 cm

Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Luis Pazos (La Plata, Buenos Aires, 1940) has based his oeuvre on conceptualism, performance and poetry associated with collaborative and collective ways of working. His impulse for street art and public intervention is always present. On this occasion, he takes Alberto Greco’s chalk circle as a reference and reformulates it to take it towards the idea of circulation. To activate the circulation of art, he proposes to give museum visitors a set of one hundred drawings that he made in 2017. While he waits for the museum to reopen so that he can carry out his action, this video shows the large variety of colours, energetic strokes and doodles contained in the drawings, and he sets about signing them. The artist considers these drawings to be like “electric shocks” charged with emotional energy, waiting for the moment they can be delivered to visitors in celebration of the bonds that art forges with its community.

BIOGRAPHY:

Luis Pazos (La Plata, Buenos Aires, 1940) is a conceptual artist, performer and poet. He has been a member of the Esmilodonte, Grupo La Plata, Movimiento Diagonal Cero, Grupo de los 13, CAYC and Grupo Escombros. In 1967, he published the book-objects El dios del laberinto and La corneta, edited by the magazine Diagonal Cero and directed by Edgardo Antonio Vigo. Together with Claudio Mangifesta, he published the visual poetry books Letra suelta [(2015), Del Silencio como mirada (2016) and La escritura de la ciudad (2020). Other published works include El cazador metafísico, Poesía reunida I (2011); Fabricante de modos de vida. Acciones, cuerpo y poesía (Document Art, 2012), written by Fernando Davis; Señor de la alucinación (2013), Poesía Reunida II. El Señor de la Alucinación y el Cantar de Godofredo de Bouillon. La espada de Dios. (2019), and Mulata (2021). His work is part of the collections of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Museo de Arte Moderno in Buenos Aires and the Centro Experimental Vigo. He received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes (2020) and the National Artistic Achievement Award 2020/2021, from the Palais de Glace.

Luis Pazos, Todo artista es un exorcista [Every artist is an exorcist], video, 2 min, 2021

Homenajes Urbanos, a collective formed by Ale Giorgga and Melisa Boratyn, has been intervening in the public space with woodcut posters since 2017. Their posters pay homage to different Argentine artists and constitute a meeting space between visual poetry and activism, using visual resources that focus on the strength of different sizes of fonts and the impact of short phrases.

Their tribute to Alberto Greco began in the streets of Valencia, Spain, and ended in Buenos Aires, in the neighbourhood of San Telmo. Through stickers, graphic representations and the forcefulness of the text, Homenajes Urbanos reclaims Greco’s presence in cityscape, which is the context in which most of his works and, crucially, vivo-dito emerged.

BIOGRAPHY:

Homenajes Urbanos is a project co-produced by Ale Giorgga (Buenos Aires,1985), BA in Museology, visual artist and member of the collective BA Paste Up, and Melisa Boratyn (Buenos Aires,1987), a curator with a Bachelor of Arts. Their project seeks to expand the limits and break certain barriers in the field of contemporary art while sharing the history of Argentine art with more people. In 2017, they selected a group of deceased artists whose works are exhibited and promoted by institutions or museums, but who are not widely recognized. They designed a disruptive system to bring them closer to the public and make them more accessible through urban interventions, words, paper and the concept of diffusion. Their tributes have included the work of Federico Manuel Peralta Ramos, Martha Dermisache, Juan Carlos Romero and Alberto Greco, among others.

Homenajes Urbanos Homenaje a Alberto Greco / EXIJO [Tribute to Alberto Greco / EXIJO],

Urban Action Video, 2019-2021

Luciana Lamothe (Mercedes, Buenos Aires, 1975) develops her oeuvre through the exploration of sculpture, installation, photography and video. This selection of photographs is a record of different acts of vandalism carried out clandestinely in public spaces of the City of Buenos Aires between 2004 and 2010. The photographs record different moments in the process of interventions of commercial premises, offices, public establishments, or motorcycles and parked cars. In some cases, the result or effect of the action is shown, such as a recently painted table, a disassembled chair, or a broken yogurt sachet sitting on a shelf full of soap. Other photographs show the action taking place, so we can see a security sticker being peeled off, a license plate being removed from a car, or a lock being broken. The images, with their tight framing and proximity to the objects turn us into inescapable witnesses and accomplices of each of the actions.

BIOGRAPHY:

Luciana Lamothe (Mercedes, Buenos Aires, 1975) participated in the XI Lyon Biennale, Lyon; the 5th Berlin Biennale, Berlin; the III Montevideo Bienniale, Montevideo, and the Vancouver Biennale (2021). She has also participated in exhibitions throughout the world, including Art Basel Miami Beach Meridians; Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien, Berlin; CGAC, Santiago de Compostela; La Maison Rouge-Fondation Antoine de Galbert, Paris; Palais de Tokyo, Paris; Museo Da Maré, Rio de Janeiro; Museo del Barrio, New York; MAMBA; Fundación PROA; MNBA, Buenos Aires.

She participated in residencies in cities such as Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Antwerp, Belgium, and Maine, United States. She was awarded the First Prize of the Lichter Art Award, Frankfurt and the Itaú Cultural First Prize, Buenos Aires. She received the Artist Fellowship from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, New York (2019) and was a fellow of the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella Artists’ Program (2011). Her work is housed in important public and private collections in Spain, the United States and Argentina.

She lives and works in Buenos Aires.

Luciana Lamothe, Intervenciones vandálicas [Acts of Vandalism], photography, 2004-2010

This is part of a project Luciano Burba (Santa María de Punilla, Córdoba, 1980) carried out between 2009 and 2010. Over the course of that year, he collected objects he saw on his way from home to work. In general, they are fragments and parts of the architecture of the past: rubble, bricks, branches, wood, tiles. Each object is labeled with a word that describes its material characteristics or the circumstances of its discovery. Words such as “rest”, “cornice”, “surface”, “wire fence”, “plain”, or “Sunday” rename the objects while giving them new meanings. The last step in the artist’s process is to invite friends to make a selection, grouping or arrangement of several of the word-objects, thus creating poems that are both visual and linguistic.

Here we share a selection of six poems that Burba made specially by arranging or grouping objects according to composition, colours, fit, or meaning of the words, such that the process is always open, ephemeral and changing.

BIOGRAPHY:

Luciano Burba (Santa María de Punilla, Córdoba, 1980) has a degree in Sculpture from the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. He has participated in solo and group exhibitions at fairs, galleries and museums in Argentina and abroad. Highlights include: Pesadillas para mesitas de noche [Nightmares for Bedside Tables] (Córdoba, 2018), Pasamos tan rápido de un lugar a otro que las cosas se mezclan [We move so fast from one place to another that things get mixed up] (Fundación Klemm, Buenos Aires, 2014), Recursos [Resources] (Espacio Cultural Museo de las Mujeres, Córdoba, 2012), Luciano Burba Retrospective (Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, 2011). In 2010, he was the recipient of the 1st CCEBA-INJUVE Award. In 2013, he won the 2nd Salon and the City of Córdoba Award. In 2017, he was a fellow of the Plataforma Futuro Program of the National Ministry of Culture. Since 2013, he has co-edited the collection “1.330.022, etcétera”, by Editorial Casa13, about contemporary artists from Córdoba.

He lives and works in Córdoba.

Luciano Burba, Vital, mínimo, móvil [Adjustable, Minimum, Living], 2009-2010,

intervened objects, variable dimensions

Mimí Laquidara (Concordia, Entre Ríos, 1989) finds inspiration for part of her work in the aesthetics of walking and wandering through the city. Cities have circulation mechanisms which, due to our sense of hurry or the distances, relegate walking to short distances or to a recreational activity. In short, walking is an exception. Nevertheless, the artist behaves like a true walker; that is, she walks without a final destination, allowing herself to be invaded by a random journey.

On these journeys, she portrays relatable, everyday objects that are found in the street and which, because they are so relatable, are often invisible and go unnoticed. She also imagines unexpected situations, in which geometric shapes or ephemeral actions slip into the leaden urban landscape. In this performance, the artist unfolds a 50-metre roll of paper along the steps of a park in the city of Rosario. It is one of her interventions which, in addition to introducing a new sign in the city, leaves behind a trace of the body that produced it, an echo of a gymnastic gesture.

BIOGRAPHY:

Mimí Laquidara (Concordia, Entre Ríos, 1989) holds a degree in Fine Arts from the Faculty of Humanities and Arts of the Universidad Nacional de Rosario (UNR). She was part of the 2012 Universidad Torcuato Di Tella Artists’ Program, coordinated by Mónica Girón in Buenos Aires. She has received several grants from the Fondo Nacional de las Artes for art analysis workshops and seminars with specialists such as Rafael Cippolini, Claudia del Río, Carlos Herrera and Ernesto Ballesteros, among others. She published Esculturas as part of the Contemporary Photography collection of Editorial Municipal de Rosario (2016). She received awards at the National Salon of Rosario and the Rosa Galisteo de Rodríguez Salon. She received a grant to participate in Escuela FLORA 2017, in Bogotá, Colombia. She attended the SOMA Educational Program 2017/2019, in Mexico City, on a grant awarded by the BECAR Cultural Program of the National Secretary of Culture and the FNA. Her work has been exhibited in Argentina, Peru, Colombia, Mexico, Spain and the United States and she has made interventions in various public and private spaces in cities such as Rosario, Bogota, Mexico City and Costa Rica.

She lives and works in Rosario, Santa Fe.

Mimí Laquidara, Despliegue [Unfolding], video, 3 min, 2021

The Alberto Greco: ¡Qué grande sos! [Alberto Greco, How Great You Are!] exhibition resonates and echoes throughout the other exhibitions and interventions at the museum. In “The Adventure of the Real”, a new proposal from Museo Moderno en Casa [Museo Moderno at Home], we revive the expansive, infectious gaze of Alberto Greco. We will be sharing different views about the possible links we can find with his legacy. We invite you to interpret his work and the exhibition beyond his material legacy; to investigate how his gestures have survived, the effect of his actions and the persistence of his words.

Two installations at the entrance to the museum are a sign of these resonances. First, in the café, there is Cotelito’s mural entitled Vuelvo como un jardín después del invierno [I return like a garden after winter] and, second, at the entrance to the courtyard and on the second floor, we can find pieces from Diana Aisenberg’s collection, Mística robótica en la economía de cristal [Mystical Robotics in the Crystal Economy]. Both works transform the architecture and the spaces: Cotelito, with his painting of organic forms in flat colors, and Diana Aisenberg, with here accumulation of small everyday objects threaded on ornamental strings. Furthermore, there is Elian Chali’s Plano inesperado [Unexpected Plane], on the exterior walls of the museum. The artist considers his work to be like “urban acupuncture,” a way of intervening in the city with a healing practice that is both visual and medicinal.

In the galleries, the works of Ulises Mazzucca in Gimnasia espiritual [Spiritual Gymnastics] are linked to Greco through the use of writing and calligraphy as biographical markers, imprecise textures and experience. At the same time, in the large installation by Nicanor Aráoz, Sueño sólido [Solid Sleep], signs of extreme and brutal vitality emerge in a link with the present, resounding Greco’s vital and provocative gestures. Finally, Elda Cerrato’s work, El día maravilloso de los pueblos [The People’s Wonderful Day], references Greco in the use of an element that is both simple and elemental: the circle. This form is used by both artists as the outline of diverse spaces of demarcation, contours of realities or political signallings.

At Museo Moderno en Casa [Museo Moderno at Home] we seek to rekindle the expansive and infectious gaze of Alberto Greco. There are resonances and echoes of his work in the other exhibitions and interventions that can be visited in the different spaces of the museum. On this occasion, we will present the meeting point between the works included in the exhibition Nicanor Aráoz: Sueño sólido [Nicanor Aráoz: Solid Sleep] and those of Alberto Greco.

Nicanor Aráoz takes a tour of the exhibition, Alberto Greco: ¡Qué grande sos! [Alberto Greco, How Great You Are!],

and shares his interpretation of the circle of informalist paintings in which he emphasizes not only their materiality and gestural language, but also the marks and signs that can be seen on the back of the works. Aráoz points out the tensions and dissolutions between the real and the virtual as a declaration of a pact with the present. In this sense, he links Greco’s group of paintings with the liquid, luminous flat screens that we find in our everyday life. Finally, the artist compares the exhibition environment that is created from the visual intensities of Greco’s paintings with his own installation, Calabozo rata frita [Fried Rat Dungeon], in which a set of neon chains construct a prison of light, creating a confining yet ethereal space.

At Museo Moderno en Casa [Museo Moderno at Home] we seek to rekindle the expansive and infectious gaze of Alberto Greco. There are resonances and echoes of his work in the other exhibitions and interventions that can be visited in the different spaces of the museum.

Here, we look at Plano inesperado [Unexpected Plane], Elian Chali’s intervention in the façade of the museum. The elastic geometry he employs in his work blurs the boundaries between the interior (the museum) and the exterior (the city). In the words of the artist, his work unfolds like the points of an urban acupuncture treatment that tries to alleviate the pain so that the city can appear in all its splendourr, reactivating circulation and sparking movement. Just as Alberto Greco singled out people or objects with a piece of chalk and produced works on a communal and expansive scale – such as in the Gran Manifiesto-Rollo arte vivo-dito [Vivo-Dito Art Manifesto-Scroll] – Elian Chali conceives the acupunctural gesture as a collective force that reactivates contexts, reconfigures neighbourhoods and points out hidden circumstances in the course of everyday life.

#GrecoModerno #MuseoModerno #santelmo

@elianchali

At Museo Moderno en Casa [Museo Moderno at Home] we seek to rekindle the expansive and infectious gaze of Alberto Greco. There are resonances and echoes of his work in the other exhibitions and interventions that can be visited in the different spaces of the museum.

Here we share three images of works by Elda Cerrato that are included in her exhibition El día maravilloso de los pueblos [The People’s Wonderful Day] and which show links with the work of Alberto Greco.

In 1972, during the dictatorship in Argentina, avant-garde artistic trends investigated and experimented with new ways of influencing the public space, blurring the boundaries between art and politics and carrying out social awareness projects.

As an artist and teacher, Elda Cerrato took an active role in the process and participated in the emblematic exhibition Arte e ideología [Art and Ideology], organized by the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAyC) that year. Distributed between Plaza Roberto Arlt, the Museo de Arte Moderno and the CAyC, most of the artworks included in the exhibition referred to the violence, political shootings and helplessness of the civil society of those years.

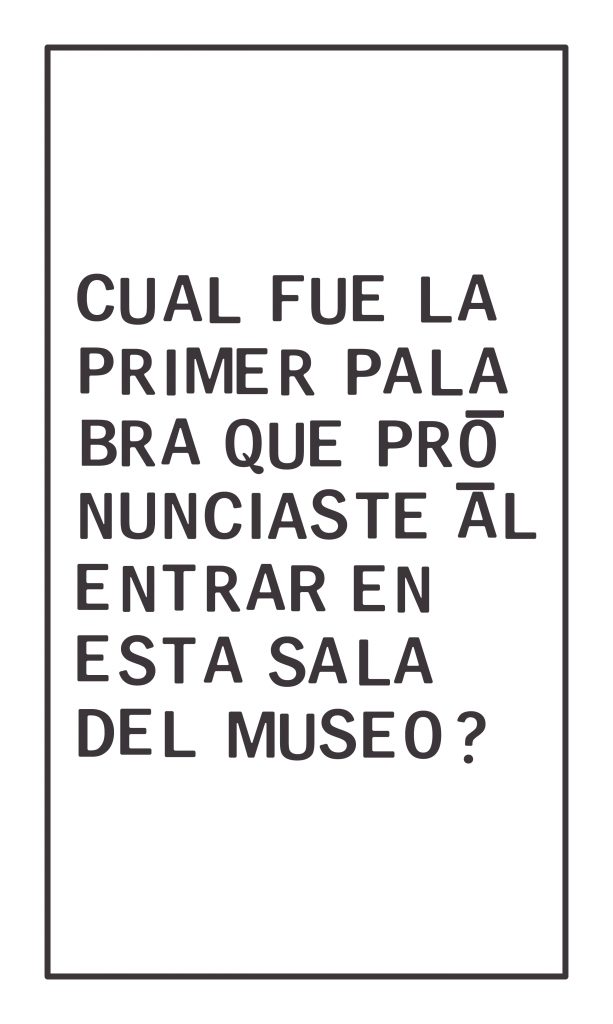

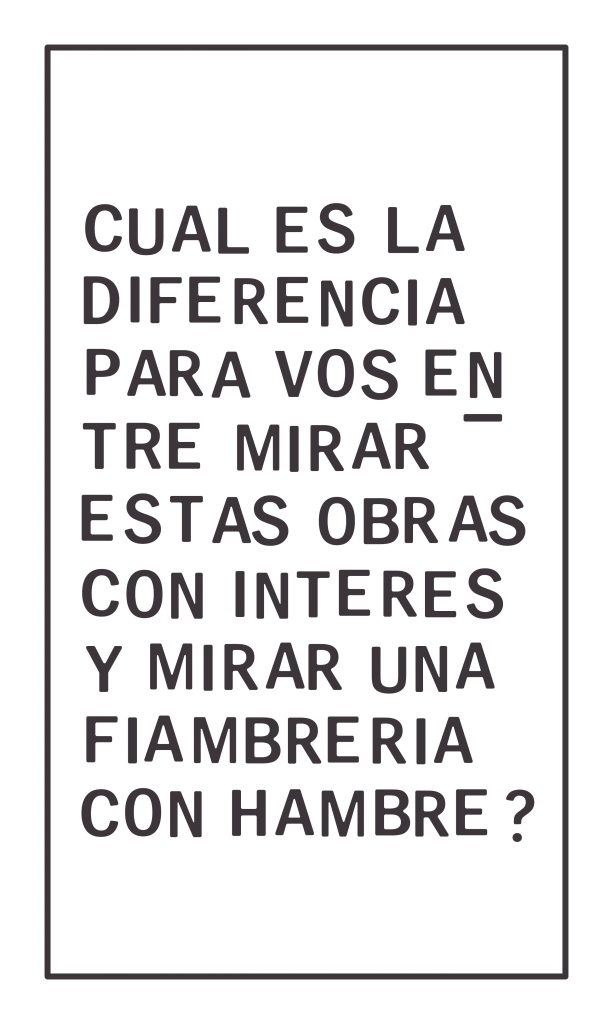

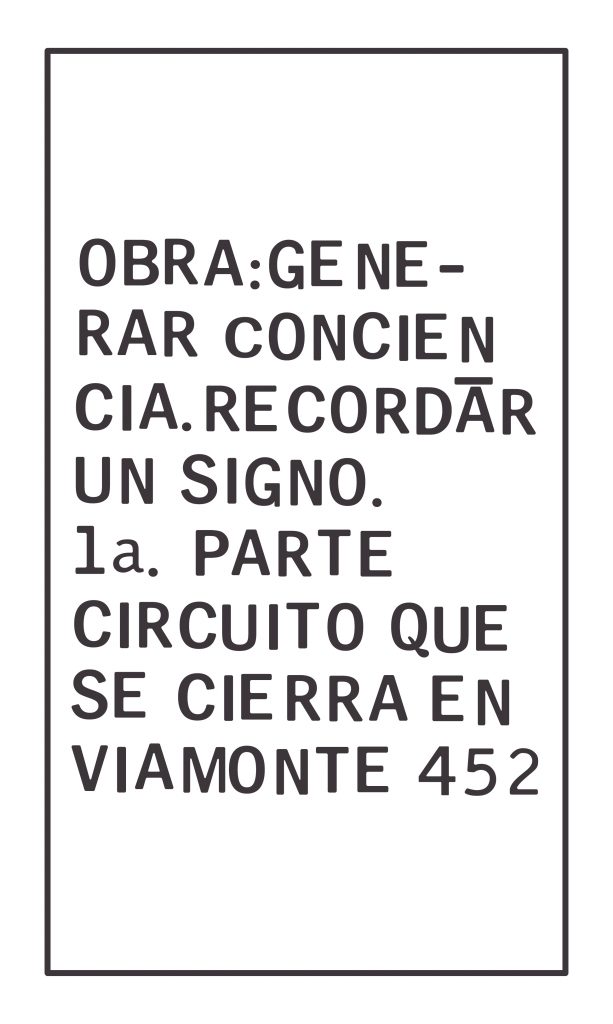

Like Greco’s urban, poster and public action in his famous undertaking, Alberto Greco ¡Qué grande sos! [Alberto Greco: How great you are!], one of Cerrato’s works for the 1972 exhibition consisted of installing advertising-type posters. In this case, the phrases on the posters addressed the public directly, challenging them to make sense of it all. By constructing a circuit between the outside and the inside of the museum, linguistically linking art and everyday life, Cerrato denounced the art institution and its public for its indifference in the face of the situation, a gesture that links to the precursor of Alberto Greco’s poster stickers.

“The adventure of the real” is the new proposal of Museo Moderno en Casa [Museo Moderno at Home] in which we revive the expansive and infectious gaze of Alberto Greco. There are resonances and echoes of his work in the other exhibitions and interventions that can be visited in the different spaces of the museum.

Here Marcos Krämer, curatorial assistant of the exhibition entitled Elda Cerrato: El día maravilloso de los pueblos [Elda Cerrato: The People’s Wonderful Day], shares some of the coincidences that can be found in her works.

In Cerrato’s work, the use of the circle acquires different values and meanings, though it can be thought of as an echo of the chalk marks Greco used to single out elements of everyday life as works of art. While in her works from the 1960s, the circles relate to an understanding of geometry and abstraction as keys to access the spiritual world, during the 1970s they begin to delineate areas that lead us to a more material reality. The same geometric forms that she employed in the previous decade are now used to encircle workers, rural scenes and popular protests. The circles are the expression of a metaphysical reality and become political inscriptions that signal precise realities and reveal the specific Latin American context to the viewer.

“The adventure of the real” is the new proposal of Museo Moderno en Casa [Museo Moderno at Home] in which we continue to revive the expansive and infectious gaze of Alberto Greco. There are resonances and echoes of his work in the other exhibitions and interventions that can be visited in the different spaces of the museum.

In the exhibition Ulises Mazzucca: Gimnasia espiritual [Ulises Mazzucca: Spiritual Gymnastics], the artworks link to Alberto Greco through the use of writing and calligraphy. The artist introduces us to his exploration of writing that he makes through his graphic and textural use of words. The link between drawing and writing appears in different media: on paper, as a texture; on furniture, as an anonymous message; and on the wall of the room, as a print. These refer to the anonymous writings left for equally anonymous recipients that can be found on park benches, bathroom doors or trees throughout the city. In his telling, Mazzucca suggests there is a coincidence with Greco’s work, in that they both link experience and biography, vital gesture and writing.