It has been almost a year since the pandemic began its spread across the globe. It has been almost a year since we began this long period of transition, of new ways of inhabiting exteriors and interiors, as we set out on a prolonged journey of changes that subverted the daily lives of some, and which have even led to an ever-deepening sensation of the imminent end of human life on earth. At the same time, we came to believe that this state of emergency would forever change the way we relate, not only to the planet but to each other. The pandemic and the circumstances surrounding it presented the opportunity to rethink the foundations of the global system that we deserve. Nevertheless, despite being closer to a lasting solution to the health crisis, the projections continue to be ominous, as if the transition that began a year ago were still underway, and more abysmal than last year.

The world continues to spin on its axis and travel around the sun, but the futures that its inhabitants imagined continue to be left on hold, with an air of uncertainty similar to a coin toss. Looking back to 2020, we can observe a recent past full of despair, lockdowns and deliberation. Looking forward, it is yet to be seen if we will once again become spectators of a world unfolding before our eyes, or if we will be able to reinvent our social bonds in order to play a leading role in the world of the future.

Art, in addition to offering alternatives, has always had the courage to closely observe the sense of chaos and loss of references. In a similar way to the artists who lived through the most distressing moments of the past centuries, the art of the past few decades has also fulfilled the task of building icons, emblems and signs that are capable of distilling the delicate hints of demise. In the weeks ahead, the Museo Moderno will bring together a group of works by artists who, in different ways, provide visual interpretations of the sensations that we are experiencing.

Artwork: Pompeyo Audivert, Lágrima [Teardrop], 1948, zincograph, 50 x 35 cm.

Collection of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

The world of Nicolás Said is similar to our own: a labyrinth full of images, references and symbols that sometimes tempt us to try and decipher and connect with it, as if it were hiding a hermetic message. At other times, it deters us and invites chaos and the belief that there is no higher meaning, let alone a clearly defined path.

His is a world similar to our own, where intimacy and the outside, the spiritual and the godforsaken, inextricably affect each other.

There is no place to hide; behind our backs, both plants and tombstones take root in the garden.

Sometimes, life and death share the same small environment, like the Radeau de la Méduse, coexisting without competing. In other moments, they are entwined in a battle over a tiny island that, perhaps, is our desire.

Artworks

All works are ink on paper.

In this audiovisual triptych by Argentine artist Mónica Heller, we witness three episodes of the life of five twigs and a match that take on the roles of fairytale characters. They are the apparent survivors of a catastrophe that may have brought about an extinction, and in each of these brief excerpts we see them traversing an apocalyptic landscape, albeit without any certain objective.

Their drifting journey is at times illuminated only by the flame of a candle – a valuable and all-powerful remnant – which allows us to see the view of what has been left behind. Through combining caustic animations with a metaphysical calm and the fantastical character of her painting, Heller constructs complex narratives in which small beings seem to lead the search and serve as the seed of possible renewal.

Mónica Heller

5 ramitas, [5 Twigs], triptych, 2018-2019

Episode 1:

5 ramitas y un fósforo [5 Twigs and a Match], 2018

1m 32s

In early 2021, when Carlos Huffmann was still in the middle of his “Pájaros doctores” [“Bird Doctors”] series of drawings, the conspiracy theory that the birds we see are not real began to catch on. Many birdwatchers, some scientists and a few military personnel from different nations began to claim, almost in unison, that birds had been wiped out by a particular strain of a virus, and what we were seeing flying between the empty buildings and plazas during the long lockdowns that swept the world were nothing more than camouflaged surveillance drones launched by the U.S. Government. A few months after Huffmann finished his series, a masked cardinal was seen for the first time descending on a U.S. town and helping with health care assistance. Given the impossibility of stopping the pandemic crisis, birds modified their functionality and exchanged their reviled covert surveillance and control operation for a form of assistance and care that was meekly accepted.

Over the course of three posts, Museo Moderno will present “Bird doctors”, Carlos Huffmann’s series of digital drawings begun during the first months of the 2020 quarantine.

Birds are perhaps the closest relatives of the dinosaurs that disappeared after the fifth mass extinction event that swept the planet. They learned to adapt to the new conditions better than any other species; they became smaller, more beautiful, their bones became lighter, their bodies more aerodynamic. This is why their genetic memory could be the key to surviving the sixth extinction event that may be caused by global warming. Perhaps it is the birds who will become the doctors of the Earth. In the early months of quarantine, when, like the rest of us, he was stuck in lockdown, Carlos Huffmann began to shape the series “Bird doctors”, which would become forty digital drawings destined for social networks and online exhibition spaces. The series emerged both from the images of the empty streets that, in our imaginations, were permeated by flocks of birds and would sooner or later be reconquered by wildlife, and from the need to rethink artistic practices and their circulation strategies, with images conceived for the same digital media that were becoming an essential part of our daily lives.

In 2021, the Museo Moderno decided to open a new collection of books of artists in digital format. We are excited and pleased to announce that “Pájaros doctores” [“Bird doctors”], by Carlos Huffmann, will be the first title released.

Reconstrucción del Retrato de Pablo Míguez [Reconstruction of the Portrait of Pablo Míguez] is the result of Claudia Fontes’ attempt to restore one of the possible images of Pablo Míguez, a victim of state terrorism in Argentina who was kidnapped when he was 14 years old. To make the piece, which floats in the waters of the Río de la Plata, Fontes began a collective process to reconstruct one of the possible portraits of Pablo Míguez, with the participation of his family, friends, 14-year-old students and forensic scientists. The figure, which sits offshore, stands with his back to visitors and viewers, in such a way that the collective reconstruction process is replicated through their participation. Míguez was born the same year as the artist, meaning that if he were still alive, he would be the same age as she is today. To create this portrait that appears to both sink into the Río de la Plata and rise out of the waters, Fontes conducted a series of interviews to gather testimonies and images of Pablo. She was in contact with his family and developed the images with a team of scientists in order to be as faithful as possible to his figure, and to contribute to constructing a collective memory of his disappearance. With his back to the viewer, the figure of Pablo Míguez reflects the surrounding waters because it is made of polished steel. Indeed, under certain weather conditions, the reflective steel means that the work cannot be seen. In this way, Fontes exposes the paradoxical condition of the simultaneous presence and absence of the bodies of the Disappeared. The placement of the piece, which, depending on the changes in the environment sometimes allows and sometimes prevents a view of the figure and what it is observing, puts the viewer in a space bordering that which has yet to take shape.

Claudia Fontes

Reconstrucción del Retrato de Pablo Míguez [Reconstruction of the Portrait of Pablo Míguez]

1999–2010

Reflections of the waters of the Río de la Plata on mirror polished stainless steel. The work is located in Parque de la Memoria, Monumento a las víctimas del terrorismo de Estado [Memorial Park, Monument to the Victims of State Terrorism], Buenos Aires.

In 2018, Argentine artist Eduardo Basualdo was invited by the initiative Art Basel Cities: Buenos Aires to produce a work in the city. He chose the pier of the Argentine Fishing Association – a windy, 800-meter-long path that slices into the Río de la Plata – in order to take visitors to the farthest possible point from the Buenos Aires coast, without losing their connection to it. At the end of the pier, a revolving door hangs from its fragile and aged edge, forcing us to confront the geographical and existential abyss that extends from that border and, at the same time, allowing us to return to our city and imagine it as a destination.

Marking bordering areas and inviting us to remain in them is a theme that appears again and again in Basualdo’s work. His works are experiences of the edges, the thresholds we find ourselves upon when surrounded by absolute darkness, light or the outdoors, when the invisible can be felt on the surface of our skin.

In this video, the artist reflects on Perspectiva de ausencia [Perspective of Absence], his project for Art Basel Cities, and shares with us his interests and the way in which this and many other of his works construct their phenomenology and particular strangeness.

On the occasion of the exhibition Fauna del país [National Fauna] dedicated to the work of Mildred Burton, renowned Argentine artist Diana Dowek reflects on the work of her dear friend, with whom she shared conversations, militancy and artistic perspectives. Dowek’s words, full of affection and meticulous observation, help us to understand that blurred boundary between fiction and reality in which Mildred Burton immersed herself, diving into the depths of the sinister and trying to uncover the dark tensions of reality.

Líbero Badíi was born in Arezzo, Italy, in 1916 and settled in Argentina around 1927, living here until his death in 2001. A visual artist with a multifaceted approach, he began his work as a sculptor in his father’s marble workshop and completed his training at the Escuela de Bellas Artes Ernesto de la Cárcova, where he also taught drawing and sculpture. His travels through Latin America and Europe allowed him to reconcile in his works the use of American iconographic symbols with his European apprenticeship experience.

In the late 1960s, he began to investigate and develop the idea of “the sinister” as a way of conceiving artistic production. According to the Latin-Spanish dictionary Nuevo Valbuena, siniestro is defined as: “left; adverse, fatal, dismal; evil, perverse; of bad omen, according to the Greek rite; and of good omen, prosperous, favorable and happy, according to the Romans.” In this way, that which opposes rational thought and escapes human possibilities became part of his artistic endeavor, not only through sculpture, but also painting and graphics.

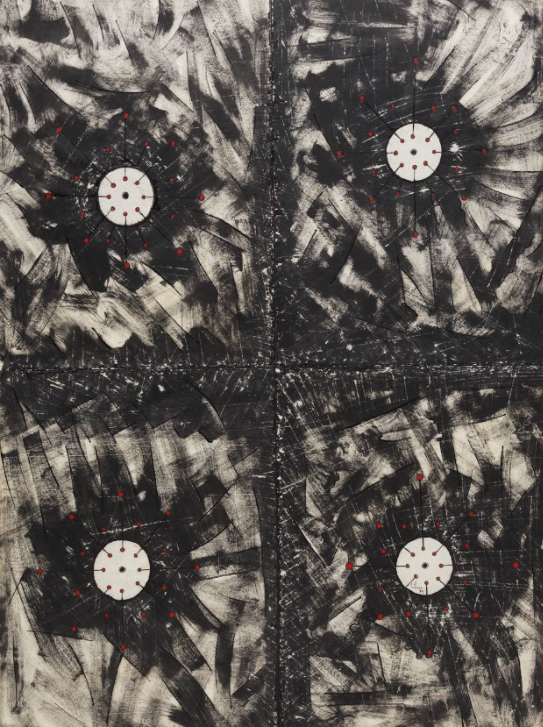

Punto en cuatro [Point in Fourths], from 1979, perhaps puts before us his continuous exploration of the uncertainty of life, of time and of our actions as individuals in society. Four quadrants, a cross, the four elements, the four cardinal points. In Andean culture, for example, this arrangement was used as an organizer of mathematical, philosophical, religious and social concepts. While many others went in search of an ordering compass, Líbero explored the mystery of existence.

Punto en cuatro [Point in Fourths], 1979

Líbero Badíi

72 x 56 cm

Mixed media

Collection of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

A left-wing political militant committed to social struggles and access to art for all, Juan Carlos Castagnino executed an oeuvre in which he developed a profound aesthetic and ideological debate. This is evidenced by his career in muralism, the testimony to the lives of rural workers and labourers that appears in his work, his strong criticism of colonialist powers, and his famous and popular illustrations for an edition of Martín Fierro, published by Eudeba in 1962.

Walking the streets of Paris during his first trip to Europe left burned in his memory the image of civilians wearing their gas masks in the midst of World War II. Two decades later, it would be the streets of a different Paris, rocked by the May 1968 unrest, that would leave a mark on his work.

Workers from different sectors joined the revolts led by the student movement, though they had different objectives in mind, which transformed the initial protests into a chaos of barricades that would become a historic event. The demonstrations – which ranged from mere wage claims within the welfare system to anti-imperialist, anti-consumerist repudiations and rejections of leadership based on cult of personality – soon spread across borders, giving rise to the largest strike across almost all of Europe and spreading, later, to Mexico, Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina. However, it was Latin America, with its long history of wars and revolutionary revolts, that inspired the collective revolutionary spirit of the French students and provided them with much of their technical knowledge about protest, for example, printing their own pamphlets. Over time, in the field of culture, this important milestone would give way to multiple readings, including that of Règis Debray, who would consider it a “successful counterrevolution”, since its demands to transform society through creativity, desire and imagination would become part of the neoliberal glossary that would establish a new individualistic conservatism.

A yawning chasm, almost an abyss, opened up between the facts of the real event and the subsequent myths. We must ask, just as the slogans that called for desire and imagination became the fuel of 21st century productivism, are the January 2021 strikes by French students demanding in-person university classes for the benefit of individual mental health at the height of a pandemic a consequence of the ever-deepening gulf between past and present rebellions?

Juan Carlos Castagnino

(Mar del Plata, 1908 – Buenos Aires, 1972)

Calle en París [Street in Paris], 1969

Intaglio and ink

65 × 46,7 cm

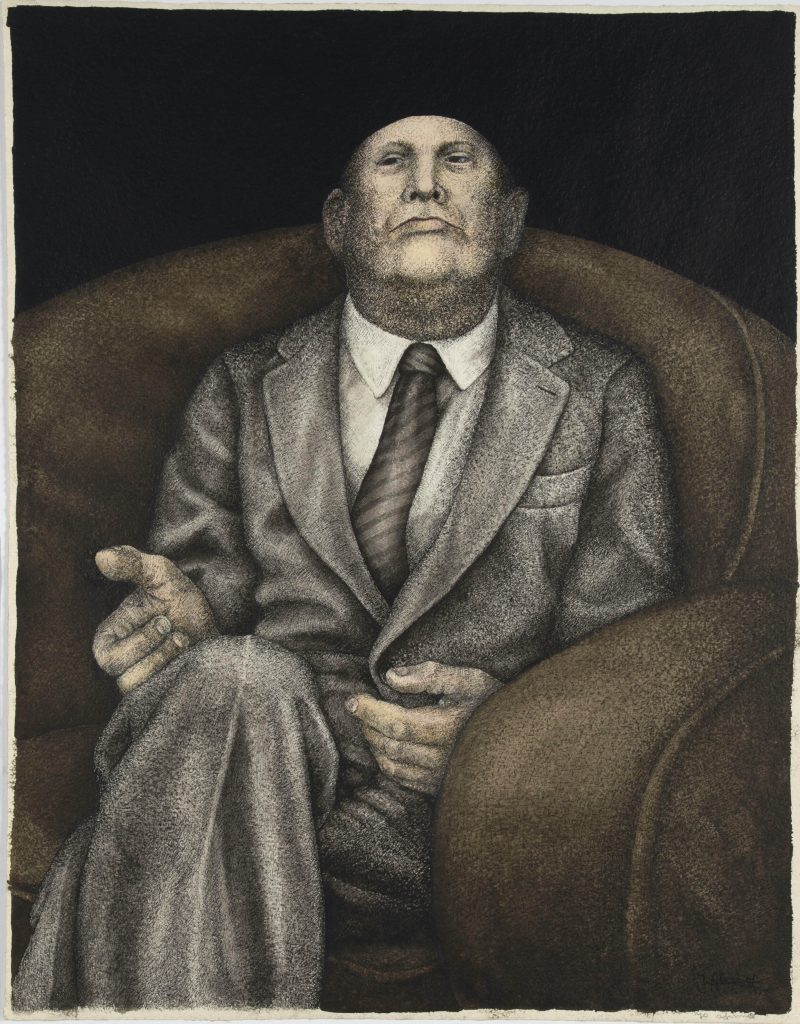

Jorge Álvaro

Yo afirmo [I affirm], 1975

Ink and gouache on paper

72 × 52 cm

Jorge Álvaro was part of Marcelo De Ridder’s generation, which was made up of artists who had returned to a traditional painting support – the canvas – and to figurative art, predominantly. Artists included, among others, Pablo Suárez, Juan Pablo Renzi, Diana Dowek and Mildred Burton. This change in the language had already been observed at the 1972 exhibition Panorama de la pintura argentina joven [Panorama of Young Argentine Painting], organized by the Fundación Lorenzutti at the museum. The Marcelo De Ridder Prize, awarded between 1973 and 1977, allowed artists under the age of 35 to gain legitimacy through exhibiting at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. Jorge Álvaro won the prize in 1975, for the category of Engraving.

The figure portrayed in this piece can be interpreted as a condensed version of the social critique that was typical of the work of these young artists of the 1970s. The man’s elusive gaze and the position of his head convey cynicism, haughtiness and the arrogance of power, while the black background behind the chair is a symbol of the growing repression and violence of society, foreshadowing the worst civilian, military and ecclesiastical dictatorship of our history.

We cannot know what he is confirming with his categorical “I affirm”. It may be a transcendental Cartesian affirmation – such as, “I affirm that I think” – or it could be a logical or an empirical affirmation.

The pandemic has pushed us into a veritable quagmire of uncertainties. It exposed our societies as sick with anxiety, not only because of the lack of certainties, but also because of the selfishness of our exacerbated individualism, the result of having been taught that our only existential driving force was addictive consumerism.

The planet continues to shake us to our foundations, but humanity’s response has been denial, the replacement of legitimate debate with rhetorical arguments that reject any positive proposal arising from scientific consensus. Thus, fake news, fake experts and conspiracy theories recreate a gesture that is perhaps as dangerous as the “I affirm” of previous years.

In this video, we invite you to get to know the work of artist Mildred Burton, to immerse yourself in the abyss between fantasy and reality. Be inspired by her works to imagine impossible connections, and to combine images to create new ones.

Share your creations with us by sending them to [email protected].

You can visit the exhibition at the museum until February 22!

We invite you to imagine your home as if it were an art museum. Working with your family or the people you live with, create different drawings and place them somewhere around your house. Follow the steps and transform your home. Make drawings of several things that interest you.

Take a tour of your home with your family or the people you live with and choose

where to place your creations. It can be the living room, kitchen, bathroom,

a corridor, or any other space. Come up together with a name for your museum. Relate the name to something in your house or to the works you created.

Take pictures with your cell phone and share them on our museum’s social media.

Given the context of today, even our most everyday actions can involve risk. Interacting with another person through a screen has taken on a distant and diffuse character. That is why the Museo Moderno is encouraging everyone to search for new ways of bonding, of creating emotional closeness through words, images and the exchange of glances.

We want to propose a different, safe way to share the museum experience. We are inviting young people to come and visit the Museo Moderno exhibitions by appointment, and then to narrate their experience in an email sent to an adult that will be assigned to them by the Education team. In turn, they will be able to give us their feedback in writing.

The invite is open to:

Young people who would like to tour, by appointment, the museum’s exhibits. Please write us at: [email protected].

Seniors who wish to participate in the activity. Please send your email address to [email protected], authorizing us to send an email from the young person assigned to you by the Museo Moderno Education team.

At the end of the experience, we will share excerpts of the stories and images on @modernoba stories.

The podcast Una obra, tres miradas [Podcast One work, three views] is a conversation among peers, featuring an artist, a museum employee and a guest from the public discussing a work from our collection.

The second edition features the participation of writer and philosopher Tamara Tenembaum, museum employee Soledad Sobrino, who worked on the publication of the exhibition catalog, and special education teacher Patricia Alonso, who provides a critical and pedagogical point of view.

Artwork: Mildred Burton, Espera en blue [Wait in Blue], 1976, featured in the exhibition Mildred Burton: Fauna del país [Mildred Burton: National Fauna] at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 2020.