Santiago Iturralde

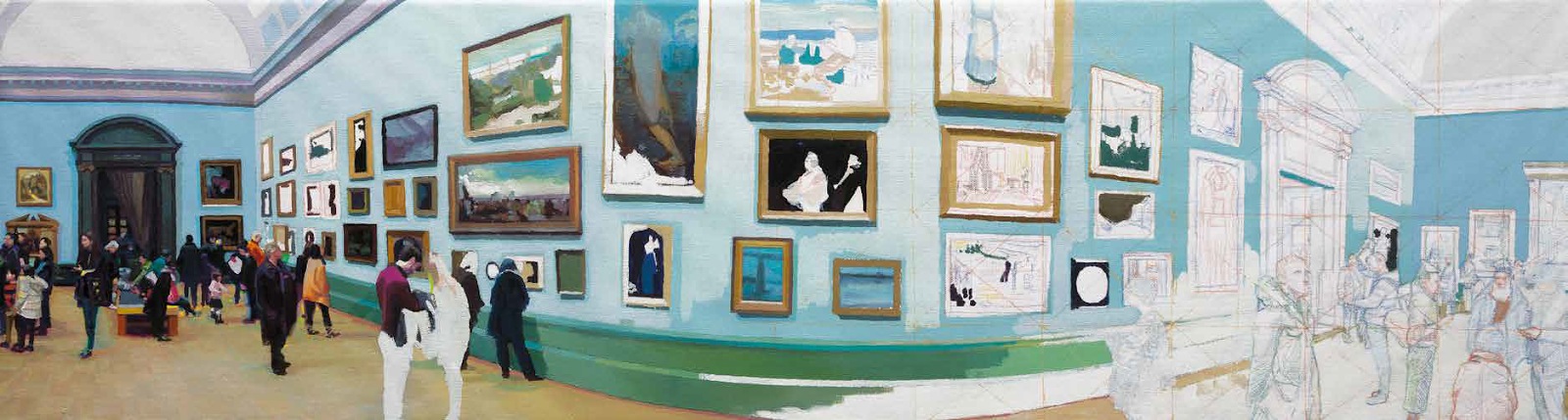

A veces un cerebro y ningún ojo, a veces un ojo y ningún cerebro [Sometimes a Brain and No Eye, Sometimes an Eye and No Brain], 2019

Óleo y lápiz sobre tela [Oil and pencil on canvas]

35 x 130 cm

What is the mission of a modern and contemporary art museum faced with a scenario like the one we are living through? How to redesign its modus operandi in order to bring home the fact that a museum is much more than its buildings, galleries and exhibitions? How to bring the hundreds of researches and proposals produced by the museum to the public at large? What is the role of the museum’s curators, conservators, producers, publishers and educators, the chief interlocutors of artists and museum-goers? What is the towering role of the artist at this time?

The quarantine imposed by COVID-19 calls on museums to reflect and galvanise beyond their doors in order to meet the needs of the communities to which, in our own case at the Moderno, the community of Argentinian artists and society as a whole – the vast majority of whom today are at home – owe their existence. We are facing a global crisis ridden with distress and uncertainty. What is the role of culture – a fundamental right of people – in times like these? What is the role of imagination and creativity? What role can artists from all disciplines play, alongside museums and art centres committed to the mission of bringing these artists’ creations to the most diverse audiences?

This week the Moderno is inviting different artists, educators and cultural intellectuals to share their works, creations and thoughts in order to shed light on the here and now, and to present their vision of the museum’s role today and what the museum of the future should look like. What will museums be like when they reopen? What strategies will they deploy to provide spaces for their employees and visitors to learn and enjoy in safety and security? How, post-pandemic, do we become healing, linstitutions? Could we – all the museums together – encourage the development of a society that is more caring, more diverse and inclusive, more accessible, more sustainable and ecological, more egalitarian and – why not – more feminist? What are the values we want to share through culture and bring to the whole of society?

Victoria Noorthoorn

This table is inspired by the cause of Maristella Svampa, who defines herself like an amphibian intellectual and an everlasting Patagonian who thinks in key Latin American. In quarantine, the great Argentine activist reaffirms, based on the analysis of the socio-ecological crisis, social movements and collective action, the great opportunity for humanity to rethink and enable a coexistence sustainable and equitable. For its part, since time immemorial art has had a utopian dimension; the best artists have always been ahead of their time and have tried and designed other ways of being in the world, away from the prevailing paradigms of the moment. Convinced about the need to think the museum and art as portals to a new, fairer, more democratic world, more ecological and more feminist, the directors of Argentine museums invited to this table share their glances and utopias, as well as those of the artists and intellectuals to who they follow closely, and the actions they promote to make them come true.

Special guests: – Maristella Svampa, Senior Researcher at Conicet and Senior Lecturer at the National University of La Plata – Fabiola Heredia, Director of the Museum of Anthropology, University National of Córdoba, Argentina – Teresa Riccardi, Director of the Eduardo Sívori Museum of Plastic Arts, Buenos Aires – Nicolás Testoni, Director of the Ferrowhite Museum-Workshop, Bahía Blanca, Argentina

Moderated by: Victoria Noorthoorn, Director of the Museum of Modern Art of Buenos Aires

Fourth meeting / Cycle Managing uncertainty

An enthusiastic conversation about the role of art, culture and museums today in Argentina and in the world. What is the contribution of museums to society? What are the values that it promotes or should it promote? The necessary self-criticism in the face of the Covid-19 crisis and the possibilities that open up in the future. The crucial role of artist in thinking about museum management.

In this cycle, the Modern Museum curatorial team presents the donations of artists and collectors, who constitute the pillars of its heritage.

In the second chapter, Marcos Krämer analyzes the group of works donated by the National Endowment for the Arts in 1968. Through the analysis of just a small handful of the most relevant pieces of that group, it is possible to understand the institutional brotherhood that existed between the FNA and el Moderno, as well as their joint vocation to support the heterogeneity of the Buenos Aires artistic field of those years. The relevance of this donation, which took place during the period in which Hugo Parpagnoli was director of the museum, lies in the varied breadth of the productions that comprise it: from an emblematic painting of the now established Emilio Petorutti to an adorable group of paintings by artists unknown that Manuel Mujica Láinez grouped under the name of “naive artists”, going through the visual experimentations of Generative Art, the first pop paintings by Nicolás García Uriburu and two pieces of textile art. This diverse feature of the donation of the National Endowment for the Arts is an imprint of the plurality of tendencies of the artistic and historical periods, but it is also a symptom of the vocation to achieve that a public collection includes all the aesthetic experiences of the time, spirit that the Modern Museum still preserves.

For one week starting on International Museum Day, Monday 18 May,

a curator from the Museo Moderno will be choosing a work from the

museum’s collection.

Hilda Mans

Síntesis [Synthesis], 1975

Oil on canvas

80 × 80 cm

Ignacio Pirovano Collection. Donated by Josefina Pirovano de Mihura. Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires.

Síntesis by Hilda Mans, donated to the Museo de Arte Moderno, is the only work by an Argentinian female artist in the Pirovano abstract art collection. Its solitary presence points up some conspicuous absences, notably that of Lidy Prati, who played a part in the vanguard of concrete art enshrined by the Collection from the outset but whose work doesn’t feature in it. This omission is probably due to Prati and Tomás Maldonado’s divorce in the early 1950s, and the close relationship between Maldonado – the Pirovano Collection’s artist and curator – and Pirovano. The artist and poet Hilda Mans was the partner of painter Victor Magariños D., with whom she moved to Pinamar in 1967. Unlike Prati, the close link between Magariños D. and Pirovano qualified Mans for a place in this collection.

Argentina’s abstract art scene was marked by male homosociality. This, coupled with the traditional limitations of women artists – privileging their male partners’ careers while shouldering domestic and family responsibilities – crystallizes in a landscape of Argentinian abstract art marked primarily by universalist, patriarchal references. We had to wait until the 1990s for mid-century abstraction to be r eviewed from a gender perspective.

Síntesis foregrounds linear segments that organise the surface, colour and space: the picture gives visible form to a moment, ‘synthesizing’ a fragment of the trajectory of these lines that continue in real space. For me, by pointing beyond itself, this painting challenges our ideas about the consolidation of selections and omissions.

María Amalia García is an Associate Curator of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires.

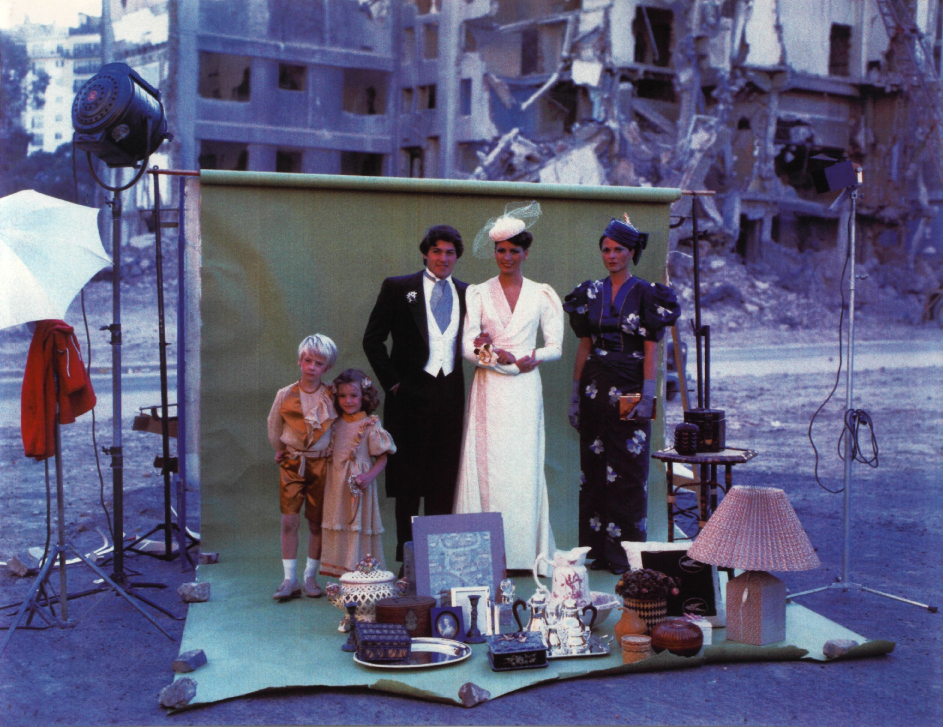

Dalila Puzzovio, Mientras unos construyen otros destruyen, 1979, copia color, 69,7 x 90 cm.

Colección Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

1979 must have been a terrible year: the Dictatorship weighed heavily on Argentina, a war with Chile seemed just around the corner and Mayor Cacciatore was laying waste to Buenos Aires. I know of no other works that provide an image of the field of rubble that was Buenos Aires in those days. Puzzovio witnessed the destruction, but also something approaching a filament of light, the will to keep going forward even when everything around us is crumbling.

Lucrecia Palacios is Curator of Public Programmes at the Museo de Arte Moderno.

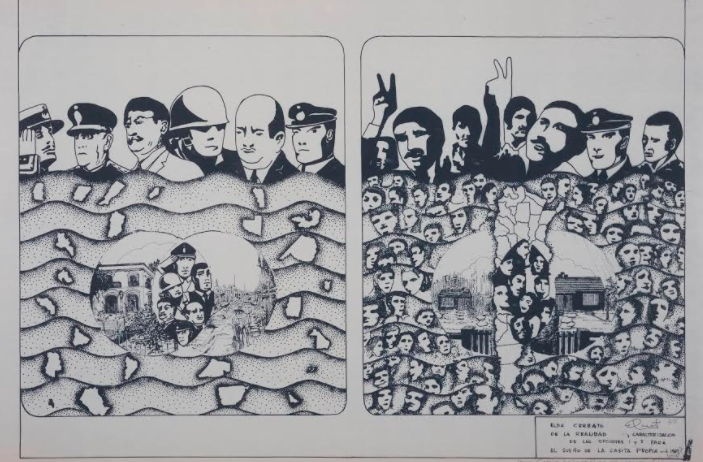

Elda Cerrato, Caracterizaciones de las opciones 1 y 2 para el sueño de la casita propia, 1972/2010, copia heliográfica 60 x 90 cm. Colección Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Elda Cerrato’s vast output begins in the 1950s and presents recurrences that place her work in the imaginary of Latin American art. This piece from the Moderno Collection dates back to the 1970s. It condenses key meanings of her work, though there are also echoes of her contemporaries: maps as symbols to think about identity and the territorial struggles of the Southern Cone; a figurative graphic style used to represent the tensions between opposing ideological projects; the undivided party-political militancy of artistic practice; and topics related to socio-economic inequalities, like access to social housing, are a few clearly located period markers. This can also be seen in the materiality: after more abstract informalist paintings and drawings made in the previous decade, Elda began this series of standardly reproducible heliographs, whose economy of resources aided their realization and circulation. Popular graphics associated with the dissemination of political slogans echoes through this piece like the burning issues of the day.

I think of this work as a testimony to the convulsive political and social context that was experienced during the civil-military dictatorships and that ever since, like almost all Elda’s work, has empowered a vibrant memory, the issue of its equally conscious and determined presence.

Carla Barbero is a Curator and Coordinator in the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires’s Curatorial Department.

Josefina Robirosa Pintura [Painting], 1957–1960 Oil on cardboard 146 x 114 cm Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires Collection

Between 1957 and 1960 Robirosa’s brush floated between abstraction and informalism. The forms she searched for in her paintings already contained the lines, light colours and graphics of her earlier images but were beginning to explore the raw textures and planes of Porteño informalism of those years.

Pintura borders somewhere on the clear energy Robirosa had been seeing since the 1950s (shot through with a kind of mysticism for which there is an invisible energy that pervades everything) and the existential darkness that fuelled informalism.

Robirosa relates that, when Kenneth Kemble invited her to join the Destructive Art Exhibition in 1961, she answered, “Look, I can’t, I’m up to my nose in water, I want to construct myself desperately.” Robirosa’s images of those years seem to stop at the point where unrecognizable forms strive to construct themselves and appear with desperation. And it is precisely over that area of impasto between the black, white and light blue of Pintura that our eyes linger most: dark, light and water at boiling point. Robirosa’s visual investigation lies not so much on the limits between abstraction and figuration but in the areas of contact between the visible and the invisible.

Several years later, when Robirosa was striving to discover abstraction in the exuberance of nature, she gave a precise definition of the artist that clarifies her understanding of painting: “An artist is like a worm, grubbing beneath the ground, digging something out, discovering or rediscovering something. Artists and worms relay one another that something – we don’t know what it is – and this never stops.”

Marcos Krämer is Assistant Curator of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Victor Grippo

Algunos oficios [Some Trades], 1976

Materials from five traditional trades (blacksmith, stone mason, builder, carpenter, farmer)

Donated by Nilda Mabel Olmos de Grippo, 2013

At a time when the discourse around what is essential is all over the front pages, the practice of work involves instances of control and authorization, and rest may – paradoxically – have taken the form of an imposition, or look like it will never to come, Algunos oficios by Victor Grippo (Buenos Aires, 1936–2002), with the captivating stealth of his works, tackles the questions that beleaguer us today around how to wield what we know or can do, our capital of exchange. A series of tools selected by the artist to represent foundational trades in society – blacksmith, carpenter, stonemason, farmer, builder – are shown at rest as if abandoned, while embodying the potential that could be tapped by their use. Grippo was an idealist, but in this work he perhaps also expresses a degree of weariness and frustration.

Algunos oficios depicts not only pause but clear division too. If in the present moment production and development depends on the great collective brain, what happens to the fragmentation of knowledge when we were alone – or less accompanied – at home? Where does our independence lie and manifest itself? What essential teachings have fallen by the wayside? Are we dependent on others or can this fragmented making become a production line of community value? And can this making be less hierarchical, more balanced in its remuneration, its demands and its rest? Can we find in the hiatus the power with which it unfolds in Grippo’s work over and over again?

Fundamentally stalled, their potential for enacting transformation – the result of any trade, but more essentially of any action – ultimately frozen, the tools in this work settle, age and wait. We might say they also think. What times, decisions and changes are now desirable to shorten, as Grippo used to wish, the distance from thought to action?’

Alejandra Aguado is a curator of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires.

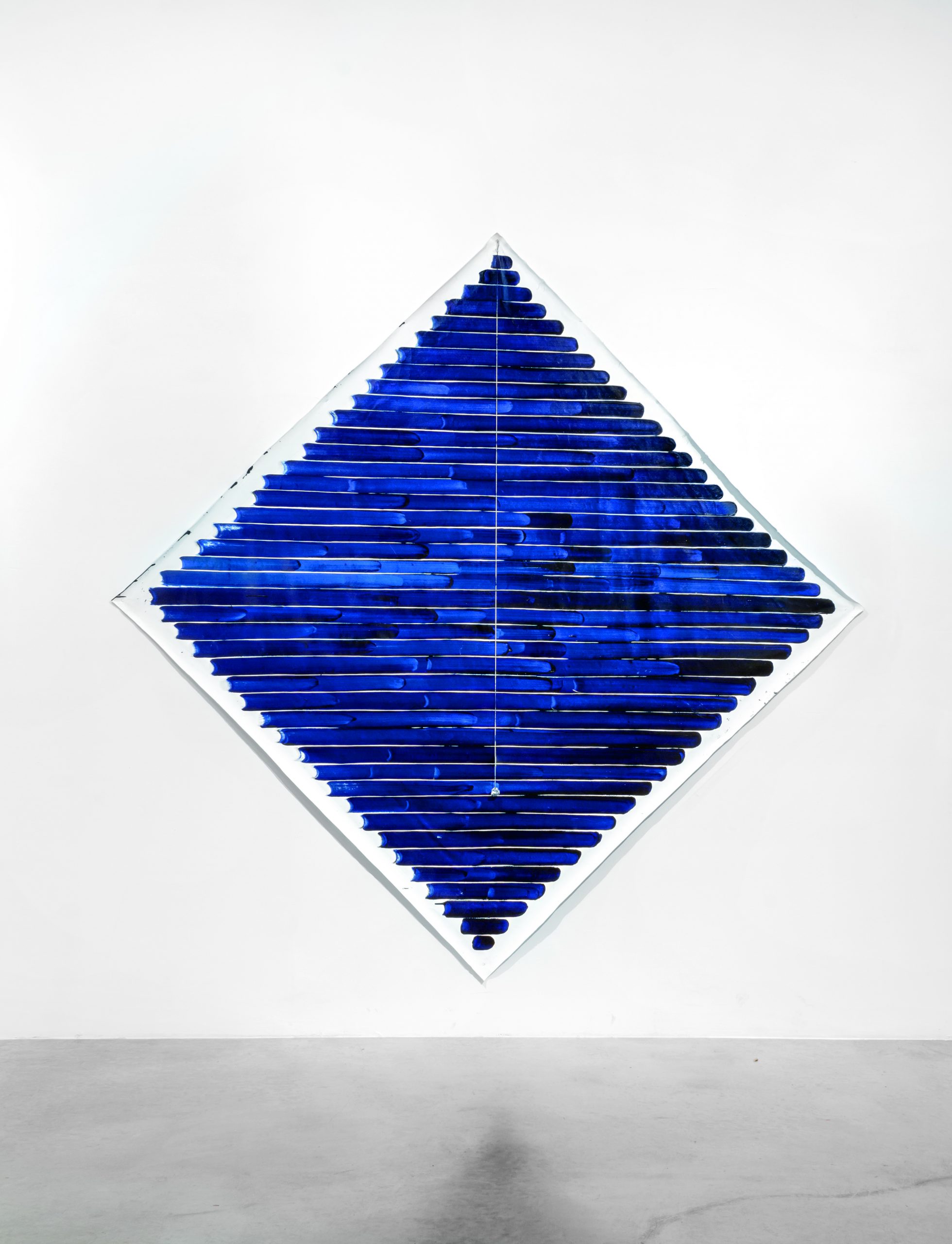

Sofía Bohtlingk

Caspar, 2013

Oil on canvas

230 x 230 cm

Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires Collection

At first glance Caspar looks almost monochrome and has a rhythm of regular lines. Rigid and rational, it seems to shout geometrical abstraction. Its key, however, is in the details: here the artist’s movements emerge, charging her brush, producing textures, pausing at the edge of the canvas, coming and going over the surface like the pendulum hanging from its apex. Slowly the blue rhombus is transformed into a form bursting with subjectivity.

It’s easy to imagine the artist dragging her brush from side to side and to observe how the blue deepens at the ends as it discharges and travels inwards from the edge of the geometric frame. Bohtlingk constructs a territory to inhabit the painting. Her body is the living geometric module moving within it: the size of the canvas is adapted to her bodily proportions, and the pendulum hangs at her exact height. I believe this abstraction is about the marks we leave in the places we inhabit. It makes me imagine my own house as one big canvas where the body forms a line drawing through its comings and goings in space, perceiving its limits, navigating time. Beneath Caspar’s coldly calculated appearance, Sofía Bohtlingk’s painting is a strange map of the body, not too unlike the folds imprinted on our sheets by our nightly dreams.

The work’s title refers to the German Romantic painter, Caspar David Friedrich, who painted characters engrossed in landscapes – oceans and mountains of bluish hues – that seem about to devour them. He was a master at representing the sublime: that emotion that rises when we feel we can’t control nature, or even begin to understand it. I kind of feel that way about abstraction.

Laura Hakel is a Curator of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Zulema Ciordia

Jules et Jim, 1961

Painted zinc plate

126 x 90 x 72 cm

1964 acquisitions

At the centre of the photo Zulema Ciordia peeps out from behind her work. Standing around her are Marta Minujín, Rubén Santantonin and Emilio Renart. I don’t recognize the others. We don’t know if Ciordia’s work still exists. The photo was taken at ‘Objeto 64’ [Object 64], the Museo de Arte Moderno’s mythical exhibition signalling the shift from painting and sculpture to the object. Photography is part of the Moderno’s document collection.

Ciordia belonged to that ’60s generation linked to the Torcuato Di Tella Institute (ITDT) and the museum. Like many others she swapped the art bookshop for the ironmonger’s, the zincworks and the timberyard. Colleagues of hers still alive have told me her projects were extremely powerful and eagerly awaited. But halfway through the decade, from one day to the next, nothing more was heard of Zulema and her works.

The second photo shows Jules et Jim, a piece of hers in the Moderno Collection. (Might it provide a clue? Is this story about a tragic love triangle?) The work was exhibited at Objeto 64 and for a second time in Diego Bianchi’s project El presente está encantador [The Enchanting Present]. Zulema’s two pipes forming a single object dialogue with a being by Bianchi consisting of the bottom halves of two showroom dummies. I think Ciordia could belong to a genealogy that ranges across artists like @enlarge2, Luciana Lamothe, Luis María Terán and many others.

Zulema’s is one of those mysteries lavished on me daily by the museum’s collection, and I share it with colleagues like Sofía Dourron and Helena Raspo. Maybe these days when we’re all so focused on screens are a good opportunity to ask around and see if anyone has any information. And to rattle the bars between museums, society, works, documents, researches, rumours and fictions . . .

Javier Villa is Senior Curator at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

This publication is a catalogue raisonné of the Ignacio Pirovano Collection,

the keystone of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires Collection. Apart

being from the fullest technical and visual exhibition of its component works,

it brings together key documents and images from the story of its formation. It

also comprehensively charts various aspects of the collection in essays by

specialists from various disciplines of research and conservation such as María

Amalia García, Marcelo E. Pacheco, Pino Monkes, Hugo Pontoriero, Wustavo

Quiroga, Valeria Semilla, María Inés Afonso Esteves and Silvia Borja.

With great joy, El Moderno receives the donation of some 60 works by Aldo Sessa, which span his 50-year bond with the museum. Thus, they will become part of the heritage of the institution, adding to the history of the donations made to the museum by the great Argentine artists. The donated photographs were selected by Victoria Noorthoorn, director of the institution, and many made up the exhibition Archivo Aldo Sessa 1958-2018: 60 years of images, which the museum presented in 2018. It is a set of iconic material from the career of the artist who covers, at the same time, a wide range of techniques, genres and research. The set includes photos taken from 1958 to the present day with different cameras and formats among them, 35 millimeters, medium format, panoramic, on black and white and color film, and the instant photo with Polaroid system; as well as digital photography with a camera and cell phone. The selected images represent many of the artist’s research on different photographic genres –among them, photojournalism and portraiture– and various themes, including Buenos Aires, the Teatro Colón, New York, travel in Argentina and around the world.

Aldo Sessa He began his training in graphic arts at his father’s printing press. At the age of 17 he made his first photographic collaborations in the press, first in the newspaper La Nación and then in La Gaceta de Tucumán. In 1962, he traveled to Los Angeles to study cinematography with Sydney Paul Solow, where he discovered color photography. He signed his first contract as an artist in 1972 with the Bonino Gallery. From there, he held more than 200 exhibitions around the world. His important collaborations with writers began in 1976 with Cosmogonías, a publication that brings together poems by Jorge Luis Borges, which was followed by others with Manuel Mujica Laínez, Ray Bradbury, Silvina Ocampo, among others. Among the numerous recognitions received throughout his life, in 1991 he was named Honorary Member of the Argentine Federation of Photographers and Full Member of the Academy of Fine Arts. In 2007, the Buenos Aires Legislature honored him with the title of “Illustrious Citizen of the city of Buenos Aires.”

Andrés Duprat y Mónica Girón

Ana Martínez Quijano y Adriana Bustos

Teresa Riccardi y Zoe Di Rienzo

Andrés Duprat y Mónica Girón