We are experiencing a re-emergence of the vocal power of humanity. The voice has grown stronger than it was before. It is not just a medium for language but a mark of identity with its different tones, timbres and registers. It brings an important facet of other people back into the present. There it is; in the voice, which our civilization has coded with emotions: cries of anguish, shouts of joy, the hesitancy of fear. The unique characteristics of the voice bring us closer together and help us to make contact with the sounds of others and everything they need to convey. The voice, in contrast to writing, is both message and body, thought and action, lending a new presence to human emotions.

As a medium for experimentation, the voice is also malleable material for the creation of sounds and rhythms, a tool with which to question language, a way of bringing remote voices from history into the here and now and a means of reaching places barred to the eyes.

The visual arts have spent over a century incorporating the sounds emitted by the voice as a material, building a better path to understanding the senses as fully as possible. Be it through oral poetry, how it overlaps with natural sounds or remembering that it is our oldest tool of expression, today the voice occupies a fundamental role in the interests of contemporary art. Aware that their voice is actually the accumulation of a long line of voices, the artist’s job is to establish a dialogue with the past through inherited forms, the present through the aesthetic choices of their contemporaries and society through projections of its future, making art an echo chamber that makes room for and amplifies all the voices that co-exist in our ears.

This week we have decided to focus on artworks and artists that explore the potential of the voice in a profound manner. Through them, we ask: How many different ways can the voice transmit emotional substance? What do the eyes see when they follow the path of sounds? How many and which voices make up the polyphony of an artistic event?

Curatorial staff at Museo Moderno

vana Vollaro, Alfaboca: miniclips vocálicos, 2004, DVD, 4’ 20’’ (selección). En colaboración con Lenora de Barros y Arnaldo Antunes.

Alfaboca (clips poéticos, mínimos e independientes entre sí) es una “conversación performática” de dos lenguas latinas muy próximas, el español y el portugués. Navegando por las fronteras sonoras entre estos idiomas, los clips exploran la dimensión visual de la voz, la palabra y el silencio. Realizada durante una residencia de la artista en San Pablo, Alfaboca indaga de manera lúdica sobre la traducción y las proximidades lingüísticas (culturales y afectivas) entre argentinos y brasileños.

Ivana Vollaro (Buenos Aires, 1971) es artista visual. Estudió Artes y Derecho en la Universidad de Buenos Aires. A principio de los años noventa asistió al taller de Mirtha Dermisache. Entre 1997 y 2008 colaboró con el proyecto Vórtice de poesía visual, experimental y sonora. En 2003 obtuvo la Beca Antorchas y se mudó a San Pablo. En 2012, realizó la residencia Capacete en Río de Janeiro. Ivana trabaja sobre los vínculos entre la palabra y la imagen, indagando en las fronteras de las formas, el lenguaje, la traducción y los errores y desencuentros que generan esos límites. Entre sus exhibiciones individuales se destacan: Una rosa, es una (2018), HACHE Galería, Buenos Aires; Sala Vip (2013) y Limites e deslizes (2009) ambas en Galería Laura Marsiaj, Río de Janeiro; Vermello, Galería Vermelho, San Pablo (2008); X-Tudo, Centro Mariantonia-USP, San Pablo (2007).

Frágil flor [Fragile Flower]

Video

2′, 10″

Mariano Gil

Bass flute, voice, art and animation

Zeke Zima

Guitar, loops and mixing

Manu Salomøn

Video editing

Seda Anac

Camera (Zeke)

Mariano Gil on Frágil flor: This project grew out of a collaboration with Zeke, who I met in 1987 when we arrived at Berklee (Boston, USA) to study. During quarantine he sent me a loop, and I added flutes and vocals, and decided to incorporate a clip of Yanis Varoufakis, which I liked both for its content and the tone of his voice. Zeke applied the finishing touches and did the final mix. Meanwhile I got a pleasant surprise: an invitation from Victoria Noorthoorn to take part in the Museo Moderno’s online content. With the help of Manu Salomøn we combined videos and animations, and this was the result: our collaboration for the theme The Voice… let the inner voice guiding us towards a more collaborative and loving world be heard. A huge thank you to all those who have taken part, and to Victoria Noorthoorn and Gaby Comte for their invitation and assistance. Specially made in Brooklyn, May 2020, for the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires.

BIOs –

Mariano Gil was born and raised in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where he graduated as a doctor. He never lost his passion for music, leading him to study flute with Alfredo Ianelli. In 1987 he moved to Boston on a scholarship from the Berklee College of Music. In 1993 he moved to Brooklyn, New York, where he has lived ever since as an active member of the art and music community. He has taken part in musical events and recordings with Kurt Rosenwinkel, Ben Street, Ethan Iverson, Chris Cheek, the Go Organic Orchestra, the Butch Morris Orchestra, Aaron Parks, Leo Genovese and other prominent musicians. As a visual artist he has been published by the New York Times. He has also produced dozens of album covers, participated in live paintings with Esperanza Spalding and exhibited his work at various New York galleries. Music has been an integral part of Zeke Zima’s life ever since he developed the use of reason. Born and raised in Buenos Aires, he moved to the United States to study at Berklee College of Music in Boston. After graduating in 1992, he moved to New York City, where he is an active member of the music community. As a guitarist he has collaborated with musicians like Marcy Playground, Brazilian Girls, Meshell Ndegeocello, Elodie Ozanne, Nic Thys, Me And The Other Guy, The Sun, the Butch Morris Orchestra, Diego García, Natalia Clavier (Thievery Corporation) and Wax Poetic (Nublu).

Ri-Chora [Laugh/Cry] Ri-Chora was born as a manuscript in coloured biro in 1975. What I remember is that I began writing with the intention of expressing in calligraphy the feeling of laughter, the belly-laugh, working in the world of interjections and onomatopoeias. The act of ‘crying with laughter’ became the leitmotif: to make a visual

poem that expressed those hybrid feelings that are somehow strange and, on paper at least, paradoxical. I still remember, at the time I composed the first block, the ‘laughter’ block, the arrangement of the interjections soon brought me back to the ‘visual sound’ of weeping – I had the insight that opposing sentiments could be expressed through the same sounds – and all that differentiated them were the emotions of happiness and sadness.

Unfortunately, I don’t have that first calligraphic draft anymore. In 1976 I was invited to take part in the alternative journal Qorpo Estranho, edited by Julio Plaza, Régis Bonvicino and Pedro Tavares de Lima, where I first published Ri-Chora and decided to display it in a typeset version, exactly as it had been presented in the group show curated by Fernanda Brenner, Riso e Lágrima não tem sotaque [Laughter and Tears Have No Accent], for Camden Council in London in 2016. In that case the visual appearance that gives the poem its meaning isn’t exactly what’s revealed by the chosen typography, but the mirror composition of the text is, as are the words ‘ri’ (laughs) and ‘chora’ (cries) at the top of each block as a kind of imperative inflection.

The recording of the voice performance of Ri-Chora was made in 2016, arranged by the musician Cid Campos (MC2 Studio), who I’ve been working with since 1994.

Lenora de Barros

Escrever por Dentro [Write Inside], 2005

Voice Performance: Lenora de Barros – Sound Treatment: Hilton Raw

Voice performance by Lenora de Barros, with sound treatment by Hilton Raw,

filmed in 2005 for the exhibition Não quero nem ver [I Don’t Even Want to See],

at the Paço das Artes, São Paulo.

Eu nao disse nada [I Didn’t Say Anything]

Photo performance by Lenora de Barros made in 1990 in Milan for the artist’s first

solo exhibition, Poesía é coisa de nada [Poetry Means Nothing], at the Mercado

Del Sale gallery.

Photography: Marcos Augusto Gonçalves

The visual poem minimosom [minimumsound], from which this project emerged, was created

by computer graphics in 1983 for the show Arte em Videotexto, curated by Julio Plaza at the

17th Bienal de São Paulo. It also appears in my first book Onde se vê [Where You Can See], 1984.

In 1976 I got the chance to read a text by Russian linguist Roman Jakobson, which I found stimulating and got me thinking about ‘fundamental sounds’. In his essay – the title of which I can’t remember unfortunately – Jakobson alludes to the curious coincidence that the word for mother in several languages starts with the bilabial sound ‘m’. This, he claims, might be related to our first repetitive lip movements suckling at our mother’s breast, movements that may be behind the first sounds we make. The word ‘mummy’ is also more often than not among the first words we utter when we take our first steps in speech, along with its sonic variants ‘mum’, ‘mamma’ etc.

The idea of the voice performance arises out of the climate of 2010, with sound designed by the musician and composer Cid Campos (MC2 Studio). It’s also inspired by a children’s game where I would try and utter a sound fragment, a minimal noise, ‘a snatch’, a sound ‘sliver’, and would spend hours obsessively hunting down that (im)possible sonority in my voice. The almost perfect Portuguese palindrome, ‘ominimosomminimo’ [literally, the minimum minimal sound], is pronounced the same in either direction; the letters o and m stand out visually and sonically, and when multiplied, may perhaps draw our attention to a sonic aspect of oral language minimum minimorum.

omínimosommínimoomínimosom

Lenora de Barros

Voice performance by Lenora de Barros, with sound treatment by Hilton Raw, filmed in 2005 for the exhibition Não quero nem ver [I Don’t Even Want to See], at the Paço das Artes, São Paulo.

Illustrator: Augusto de Campos, Todos os sons [All Sounds]

–

Lenora de Barros is a Brazilian artist and poet. She studied linguistics at the University of São Paulo before establishing herself as an artist in the 1970s and has remained committed to exploring language through a variety of media, including video, performance, photography and installation. Barros began her career producing visual poetry. Her early works were influenced by concrete poetry, particularly the Noigandrés Group, incorporating body art, pop art and conceptual art techniques. Her work has evolved to focus on the sonority of words, particularly through sound installations and voice performances.

Narcissa Hirsch. Taller [Studio], 1971, 16mm colour film, 10′ 00″

Direction: Narcissa Hirsch English Version with Horacio Maira Camera: Narcissa Hirsch

In this key piece of the history of Argentinian experimental cinema Narcissa

Hirsch paints a portrait of her life, memories and career as a film-maker. While

the frame of her camera remains fixed on one of the walls of her studio, a

voice-over of the artist relates the objects and images we can see and those

we don’t.

Agá [Aitch]. A poem from 1997, appearing in Dois ou mais corpos no mesmo espaço [Two or More Bodies in the Same Space] (Editora Perspectiva, São Paulo). A recording of the performance staged in 2016, at the SESC Palladium, Belo Horizonte.

Arnaldo Antunes was born in São Paulo in 1960, when Oswald de Andrade’s Anthropophagy and Haroldo de Campos and Décio Pignatari’s Concretism movements formed part of the everyday landscape of Brazilian culture, and Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil were taking their first steps in Tropicália fusion. Poetry, music, visual art, performance are just a few of the many terms we can use to identify the contraband of signs that defines Antunes’s work. He is genuinely unclassifiable figure who has made the slippage between languages the cornerstone of his creative procedures. He has more than ten book titles to his credit and a prolific musical career as a soloist, band member with Os Titãs and Tribalistas, and has collaborated with musicians like Laurie Anderson, David Byrne and Ryuichi Sakamoto. His work displays an unusual talent for combining daring avant-garde experiments with the aesthetics of popular culture, both in his records, books, performances and visual works, and in his installations, videos or concerts.

A playlist put together by the curators of the Escuchar [Sonidos visuales] [Listen [Visual Sounds]] Festival, Jorge Haro and Leandro Frias, to add to the theme of the week of the Museo Moderno en Casa [Moderno Museum at Home]. A tour of vocal works comprising unmissable tracks, cult experiments, the complex textures of The Bulgarian Voices, pop approaches, Zen and ancestral music.

POW!, 2014–2018, video animation, 7′, 45″, Loop (excerpt)

An animated football both embodies and performs a script that casts its net of reference far and wide: the passionate football commentator Omar Bentancor describing a famous goal by Chuco Sosa for Argentinos Junior against San Lorenzo; the gratingly calm intonations of two yoga teachers; an obsessive mother’s collection of phrases; the ferocious struggle between Captain America and Wonder Woman in the conversation of a child. The work seeks an oral form for what could be interpreted as a sign of excessive force in our everyday spoken language.

The original piece was performed at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) in March 2014 as part of It Makes Us Think of a Dance and a Fête as Much as of War (On Violence), a series of international symposia ahead of Ireland’s EVA International Biennial of Visual Art. The video animation was produced by the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires for the exhibition Mercedes Azpilicueta: Cuerpos Pájaro [Mercedes Azpilicueta: Body Birds], Buenos Aires (November 2018–April 2019).

Credits: Mercedes Azpilicueta (concept, text and voice)/ Azul Demonte (animation and 3D modelling)/ Tiago Worm Tirone (voice recording and sound editing)

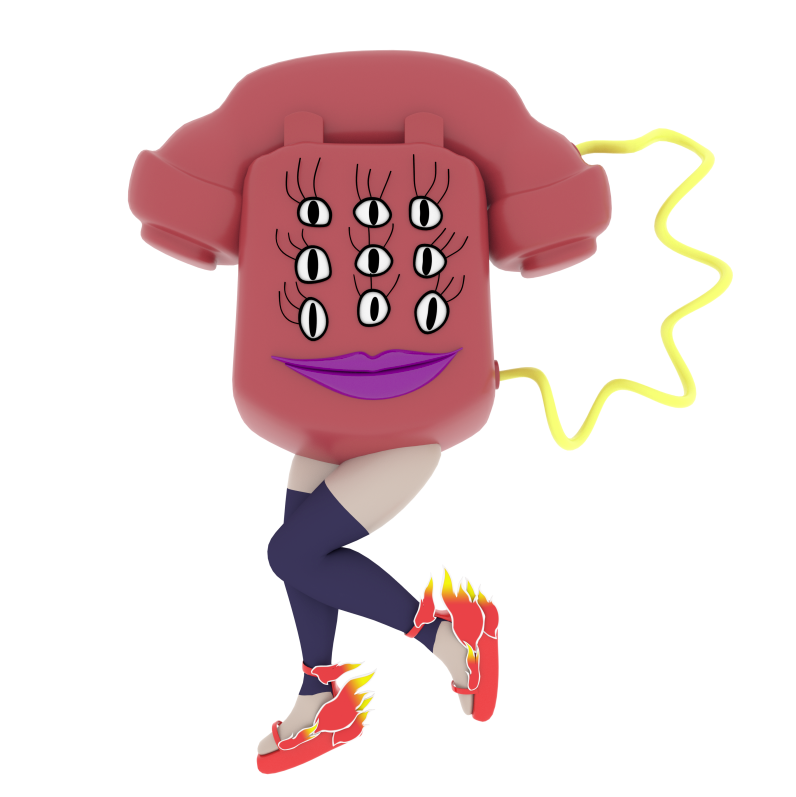

An animated telephone both embodies and performs a script that poetically combines a year’s text messages taken from a mobile phone between Buenos Aires and Amsterdam from July 2010 to July 2011. The juxtaposition of messages and poetry enacts the possibilities and impossibilities of communicating with others.

The piece was originally performed at the Dutch Art Institute (DAI), Arnhem, in June 2012, again in Lost & Found at the Theatrum Anatomicum of Waag Society, Amsterdam, in December 2012, and later in The Poetry Readings Program at documenta 13, Offener Kanal Café, Kassel. The video animation was produced by the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires for the exhibition Mercedes Azpilicueta: Cuerpos Pájaro [Mercedes Azpilicueta: Body Birds], Buenos Aires (November 2018–April 2019).

Credits: Mercedes Azpilicueta (concept, text and voice)/ Azul Demonte (animation and 3D modelling)/ Tiago Worm Tirone (voice recording and sound editing)

Volver a casa expandiendo la voz, 2012 – 2018. Video

animación, 8:30, loop (extracto)(extracto)

Carne [Flesh], 2013–2018; Video animation, 6′ 40″, Loop (excerpt)

An animated cheese-grater performs a script that poetically combines pharmaceutical vocabulary (especially chemical reactions), definitions of tear gas, the songs of Rotterdam market vendors, a list of different types of meat and cooking utensils, and e-mail greetings and envois.

The script was originally performed at the Dutch Art Institute Istanbul (DAII) exhibition at Galata Fotoğrasanesi Fotoğraf Akademisi, Istanbul, in September 2013. The video animation was produced by the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires for the exhibition Mercedes Azpilicueta: Cuerpos Pájaro [Mercedes Azpilicueta: Body Birds], Buenos Aires (November 2018–April 2019).

Credits: Mercedes Azpilicueta (concept, text and voice) Azul Demonte (animation and 3D modelling) Tiago Worm Tirone (voice recording and sound editing)

This book traces a path through the main lines of interest in Andrés Aizicovich’s work, featuring many of his drawings, writings, sketches and images of a variety of works from his output. Accompanying this material are documentary photographs from Contacto [Contact], the exhibition of his work at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires in 2019. It also features a curatorial text by Laura Hakel, an extended essay by Francisco Ali-Brouchoud, a biography of the artist and a glossary defining the essential concepts of the artist’s work.

Andrés Aizicovich

Habla para que pueda verte [Speak So that I Can See You], 2020.

Video, 2′ 35″

Credits: Andrés Aizicovich (concept, texts, voice)

Natalia Labaké (montage, sound editing, voice)

Ivo Aichenbaum (voice)

This week we have decided to highlight the idea of the human museum, sustained by the emotions of its workers and viewers, who interact with the institution in different ways. We would therefore like to bring you a publication jointly designed by the gallery guards of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires and its Education Team. The Team’s testimonies arose out of the weekly meetings motivated by the need to meet and keep thinking about the museum collectively. We thank all the voices who have breathed life into this collective creation: Bárbara Arona, Victoria Martín Reyes, Victoria Renzo, Paula Forgione, Fabián Bracca, Agustina Bracca, Silvia Benítez.

The publication is also illustrated with a selection of drawings by Hernán Barreto, one of the historic guards at the Moderno, who has documented every exhibition to pass through our galleries in the last five years in more than six sketchbooks. We recognize the importance of records in these virtual times, when information can feel extremely ephemeral. How do drawings contain time?

We hope you enjoy this exploration as much as we have and will soon be back at the Moderno to contemplate other ways of looking.