From his home in lockdown in Montevideo, this unclassifiable Uruguayan writer, musician and composer presents a mini-show specially created for the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires. Witty texts and songs that cross his relentlessly experimental and curious outlook with popular culture, classical and contemporary composition, exquisite performances and the word that takes apart the mechanics of sentences and meanings with fierce tenderness.

In February 1962, Alberto Greco was invited to take part in an exhibition of thirty Argentine artists ‘from the new generation’ in Paris. His work consisted of presenting thirty foul-smelling rodents in a box under the title 30 Rats from the New Generation. And so with the insolent, revelatory power of the joke, his ‘living art’ was born. Federico Manuel Peralta Ramos took a similarly playful approach to words and concepts when in 1974 he made the ‘Collective Subconscious of the Country’ a reality by selling a replica of a mailbox – a reference to a popular saying – at an exhibition. Humour as a means of criticizing the clichés of the artistic institution and society is a key way of keeping art vibrant and vital.

Is humour a part of art, is art possible without humour? In his famous text Laughter, the philosopher Henri Bergson noted that the comic is aesthetic in itself as it ‘comes into being just when society and the individual, freed from the worry of self-preservation, begin to regard themselves as works of art.’ According to Bergson, laughter is the means by which humanity frees itself from the rigidity of the body and the thoughts that dominate when one fears for safety, struggles for survival and is wary of imminent tragedy. Freud saw humour as a strategy for releasing the tension of a hidden truth repressed in one’s subconscious. With this vein of thought in mind, it is difficult to conceive of a human experience that has more in common with the strategies of contemporary art: criticism of the establishment and profanation of solemnity, the appearance of the unexpected and introduction to new meanings, the reorganization of the laws of the world, and the search for the truths hidden beneath the surface of the everyday world. Without a degree of parody, irony or at least a playfulness with regard to traditional forms, it is hard to see how new forms and original concepts can arise that will allow us to envisage things we do not yet understand.

The humorous power of an image like Asado en Mendiolaza [Barbecue in Mendiolaza] by Marcos López lies in the parody of one of the iconic artworks in the western canon and the way it challenges set modes of beauty and presents new ones while also recovering a lost truth with the profanation of a religious image and reaffirmation of the secular ‘communion’ of friendship that had been lost under the cloak of solemnity. Even work as critical and mordant toward western civilization as that made by León Ferrari would be impossible without the humorous gesture of

“Es dibujante y es poeta y sonríe cuando se lo dicen”

Fermín Eguía

placing powerful historical figures in unexpected places, next to objects that undermine their symbolic power and images that say what they would prefer to deny.

In the presence of the scourge of rigid, close-minded thought and the solemnity of power, humour offers a new, liberated space. As Mikhail Bakhtin, says “laughter can never be converted into an instrument of oppression or brutalization. It can never be made official, it was always a weapon of liberation in the hands of the people.’ When art turns everything upside down and achieves that same degree of liberty, it makes common cause with humour in the quest to recover the lost beauty of humanity.

End of the world images and surviving art

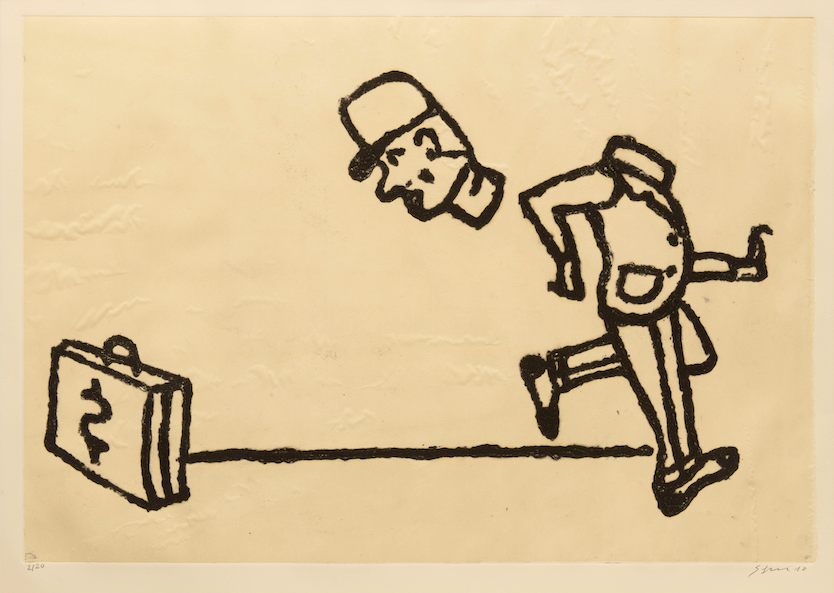

The poet and cartoonist Fermín Eguía is, in one sense, an artist straight out of the fine-art canon. Yet his work is confrontational and constantly calls this legacy into question. The logic of his images clashes with the rarefication of everyday objects and environments, and with the word, which cowers in captions, posters or notes. . . It is these slippages of meaning that spark hilarity in his works. The learned quotation, the wry metaphor, the wicked irony are the tools Eguía uses not only to avoid solemnity about art and art history, but to speculate about its death. His original world, unfolding through the virtuoso use of watercolour, is formed by a fanciful – and caustic – iconography of beings with big noses and big teeth, insect-cars, and loaves of bread and tea-pots that grow hands and feet. This strangeness traces a continuity of energies that connect Eguía both to 1930s Surrealism and its predecessor Metaphysical Painting, and with medieval Flemish painters like Hieronymus Bosch.

Fermin Eguía was born in Comodoro Rivadavia, Chubut Province, in 1942, and currently lives and works in Buenos Aires. As a young man he studied at the Municipal School of Arts and Crafts in Buenos Aires and the National School of Fine Art. His work bears a close affinity to the engraver Aída Carballo’s, with whom he studied. Since 1965 he has held regularly exhibitions in Buenos Aires, and since 1976, numerous group exhibitions overseas. His stays in the Tigre Delta outside Buenos Aires inspired most of his fantastic landscapes, while his urban landscapes feature aspects of the cities of Buenos Aires and Montevideo. In 2005 he held a retrospective at the Recoleta Cultural Centre, in Buenos Aires, accompanied by a major publication. He has been awarded several major prizes over the course of his career, including the National Salon of Painting’s 2011 Grand Prix.

1. El libreto [The Libretto], c. 2004, pen on paper, 14.5 x 21 cm

2. Paseo [Promenade], c. 2000, gouache on paper, 23 x 31.5 cm

3. Murga, c. 1998, watercolour on paper, 48 x 56 cm

4. Teatrum vinosum, c. 2006, coloured pencil on paper, 26.5 x 36 cm

5. Tertulia [Gathering], undated, pencil on paper, 15 x 16 cm

6. Julepes [Scares], c. 2005, coloured pencil on paper, 25.5 x 37 cm.

7. El pintor, la muerte y el diablo [The Painter, Death and The Devil], c. 2004, pencil on paper, 21 x 14.5 cm

8. ¡Que se lo lleve! [Take It Away!], c. 2010, watercolour on paper, 18 x 24 cm

9. ¡Sígueme! [Follow Me!], 1996, watercolour on paper, 42 x 56 cm

10. Alada fama [Winged Fame], 1987, watercolour on paper, 19 x 34 cm

11. Ex voto, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 30 x 45 cm

Yo estoy acá porque te quiero [I’m Here Because I Love You]

Back in the early 1970s, when the CAyC – Centre for Art and Communication

– was insisting on technology-based systems art and mathematics in the

construction of its works, Federico Manuel Peralta Ramos used to take part in

Tato Bores comedy sketches. He would declaim poems and aphorisms, his gaze

lost in an invisible heaven. Peralta Ramos brought a model of the artist never

before seen to television: someone who distanced himself from the intellectual

and politically committed artists of previous decades. This was an artist who

destabilized any rational discourse and contemplated the marriage of the most

irreconcilable concepts in language that crackled with wordplay, paradox

and ambiguity.

*Esta obra fue realizada por el artista Afroargentino Hector Oscar Mayato junto a Carmen Bonino, parte del Grupo Cosmos. Rojo astral, óleo sobre papel de escenografía pegado en tela, 117 x 158,5 cm. Adquisicion, 1963

Alberto Passolini

Yo soy aquel que no es Raphael [I’m The One Who Isn’t Raphael], 2020

Oral interventions on biographical photographs

13′, 39″

It is common knowledge that, for some time now, every artist has had to use

PowerPoint to display their work. Alberto Passolini decided to put together

a delirious PowerPoint presentation that muses about distance, reveals his

strategies for artistic promotion and ironises about the requirement to design

ourselves for the networks.

Alberto Passolini (Buenos Aires, 1968) is a self-taught visual artist. He has held a number

of solo shows and, since 2007, has been developing a cycle of reflections on the history

of Argentinian art. His work makes use of re-readings of historiographical texts

and landmark artworks. In the same period he has been working on a series that explores

the tension between calligraphy and drawing, and the composition of chromatic standards.

He lives and works in Southern Patagonia.

Contar chistes en un contexto poco amable, poco ambicioso pero exigente [Telling Jokes in a Unkind, Unambitious but Demanding Environment]

Somewhere between failed stand-up, cookery programme and conspiracy theory,

a woman attempts to tell four jokes with her eyes closed. They reveal the work

relations that bind employees to their bosses, their fellow workers and each other

to build up a picture of insane power structures in which oppression, freedom,

desire, callousness and love become rarefied and confused as the presenter’s

speech gradually loses focus and clarity. As in many of her works, Liv Schulman’s

character displays a gradually weakening of language skills and faltering ability to

comprehend and engage with the world around her.

Liv Schulman

Contar chistes en un contexto poco amable,

poco ambicioso pero exigente [Telling Jokes

in a Unkind, Unambitious but Demanding Environment]

Video-performance

13′, 02″

Alberto Passolini

Yo soy aquel que no es Raphael, 2020

Intervenciones orales sobre fotografías biográficas

13:39 min

The contribution from Escuchar [Sonidos visuales] [Listen [Visual Sounds]] for

this week devoted to humour is a playlist focusing on the stylistic bloc of rock,

pop and electronica, and the video-clip as an audio-visual format for circulation

and promotion. A stroll through some pieces that have made history and other

more recent ones. In their own understated or brutal ways, they all make use

of humour as a means to amplify meaning. Dance, performance, costume,

animated dolls, effects, subtleties and other bizarre details.

Curated by Jorge Haro and Leandro Frías