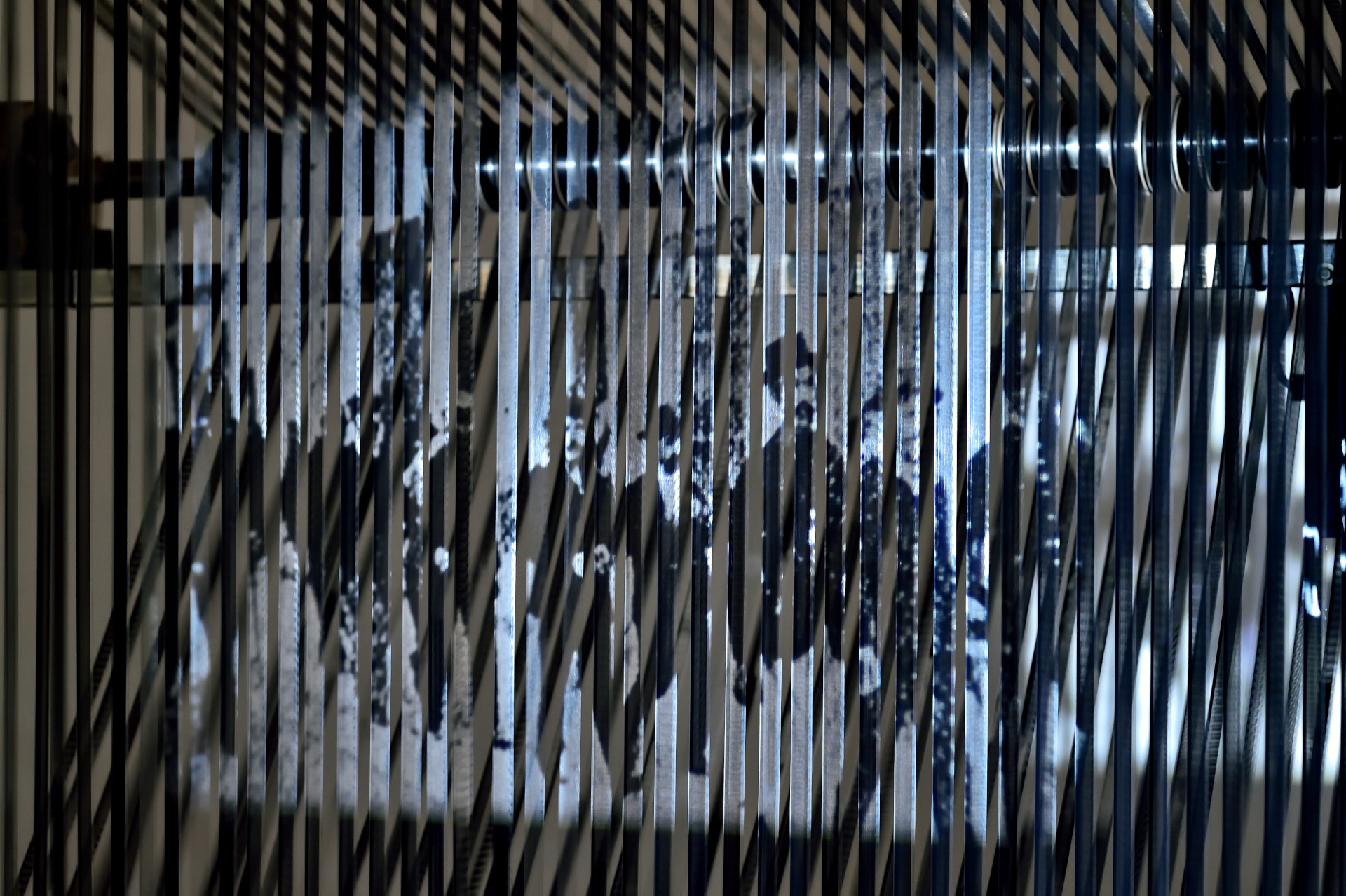

Coming from a cinema background, Andrés Denegri supplements his investigations with photography, video image, and new technologies, forming an expressive process that covers a wide range of audiovisual techniques, from single-channel pieces to installation art. The reclamation of cinema equipment from the past comes up against the proposal of constant progress as an ideological effect of a market that needs compulsive consumption in the face of the rapid obsolescence of its products. In its electro/mechanical/photochemical materiality, the Aurora project reflects on the audiovisual and appeals to the art of the memory both in its resulting images and in the paraphernalia of the equipment on display. The term “mise en scène”—which takes us back to its theatrical origin and its cinematographic aspect—takes up the basis of a perception marked by the material elements of cinema functioning in the art space. The film installation space, which presents these technological sculptures from a memory anchored in the act of watching films at the cinema, migrates to the museum and makes evident the mechanism of formation and memory of those images of the past. So it is that the process of appropriation and reclaiming of film archives, their new digital recording and the return to the photochemical medium is revealed in the form of art installation. A message is sent in the deployment of the equipment, the running of the film, the light beam coming out of the projectors and the resulting image of a combined process between different media. This is a cinema whose content is situated on the edges of narrative, and whose enigmatic, minimalist message is focused on these machines operating, in the parade of images and in the spectator observing while moving. Unlike simulated cinema, or cinema effect, common at galleries and museums, this is a projected cinema which, like never before, is situated at the centre of the exhibition space. The documentary question that the works pose is diversified or “expands”, detouring from the indicial value (or initial value? or is it from index?) of the images and their realist effect. The non-fiction status is relativized in these minimalist versions in their break with what is figurative, classical narration and their linear exposition. The passage between the supports, the moving of the device and the measure of the short running time in a loop are some of the strategies to which will be gradually added the significant wear on all the materials throughout the exhibition. The mise-en-scène consists of the absence of the projection booth, where the cinema projector would normally be shut away. The presence of the machines is exacerbated by the elimination of divisions between the works. (…) An exhibition in filming whose mechano-electrical/photochemical works will be gradually and irreversibly spoiled. The stretching and running of the celluloid, the friction of the gears and bearings and the temperature of the lights will all take their toll over the course of the exhibition. Unlike oftrepeated digital transfers, with no apparent deteriorations, cinema will see—on every day of the exhibition—its materiality deteriorate. But these are the results of its validity and vitality, attributes that this exhibition puts out there and shows to the spectator, so that they might take away this cinema in their consciousness.

Denegri Andrés

Denegri Andrés